Abu Nidal

Abu Nidal | |

|---|---|

| أبو نضال | |

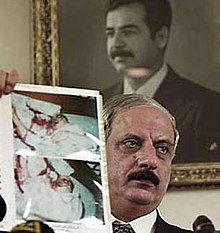

Abu Nidal in an image released in 1976 | |

| Born | Sabri Khalil al-Banna May 1937 |

| Died | 16 August 2002 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Al-Karakh Islamic cemetery, Baghdad |

| Nationality | Palestinian |

| Organization | Fatah: The Revolutionary Council (known as the Abu Nidal Organization) |

| Political party | Ba'ath Party (1955–1967) Fatah (1967–1974) Fatah Revolutionary Council (1974–2002) |

| Movement | Rejectionist Front |

Sabri Khalil al-Banna (Arabic: صبري خليل البنا; May 1937 – 16 August 2002), known by his nom de guerre Abu Nidal ("father of struggle"),[1] was a Palestinian militant. He was the founder of Fatah: The Revolutionary Council (Arabic: فتح المجلس الثوري), a militant Palestinian splinter group more commonly known as the Abu Nidal Organization (ANO).[2] Abu Nidal formed the ANO in October 1974 after splitting from Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[3]

Abu Nidal is believed to have ordered attacks in 20 countries, killing over 300 and injuring over 650 while acting as a freelance contractor.[4][5][6] The group's operations included the Rome and Vienna airport attacks on 27 December 1985, when gunmen opened fire on passengers in simultaneous shootings at El Al ticket counters, killing 20. At the height of its militancy in the 1970s and 1980s, the ANO was widely regarded as the most ruthless of the Palestinian groups.[7][8][4][9] Palestinian leadership long suspected that Israeli Mossad had infiltrated the ANO, with Abu Nidal himself having been on the CIA payroll.[10][11][12]

Abu Nidal died after a shooting in his Baghdad apartment in August 2002. Palestinian sources believed he was killed on the orders of Saddam Hussein, while Iraqi officials insisted he had committed suicide during an interrogation.[13][14]

Early life

Sabri Khalil al-Banna was born in May 1937 in Jaffa, on the Mediterranean coast of what was then the British Mandate of Palestine. His father, Hajj Khalil al-Banna, owned 6,000 acres (24 km2) of orange groves situated between Jaffa and Majdal (now Ashkelon in Israel).[15] The family lived in luxury in a three-storey stone house near the beach, later used as an Israeli military court.[16] Muhammad Khalil al-Banna, Abu Nidal's brother, told Yossi Melman:

My father ... was the richest man in Palestine. He marketed about ten percent of all the citrus crops sent from Palestine to Europe—especially to England and Germany. He owned a summer house in Marseilles, France, and another house in İskenderun, then in Syria and afterwards Turkey, and a number of houses in Palestine itself. Most of the time we lived in Jaffa. Our house had about twenty rooms, and we children would go down to swim in the sea. We also had stables with Arabian horses, and one of our homes in Ashkelon even had a large swimming pool. I think we must have been the only family in Palestine with a private swimming pool.[17]

The kibbutz named Ramat Hakovesh has to this day a tract of land known as "the al-Banna orchard". ...My brothers and I still preserve the documents showing our ownership of the property, even though we know full well that we and our children have no chance of getting it back.

Khalil al-Banna's wealth allowed him to take several wives. In an interview with Der Spiegel, Sabri stated his father had 13 wives, 17 sons and 8 daughters. Melman writes that Sabri's mother, an Alawite, was the eighth wife.[19] She had been one of the family's maids as a 16-year-old girl. The family disapproved of the marriage, according to Patrick Seale and, as a result, Sabri Khalil's 12th child, was apparently looked down on by his older siblings, although in later life the relationships were repaired.[20]

In 1944 or 1945, his father sent him to Collège des Frères de Jaffa, a French mission school, which he attended for one year.[18] When his father died in 1945, when Sabri was seven years old, the family turned his mother out of the house.[20] His brothers took him out of the mission school and enrolled him instead in a prestigious, private Muslim school in Jerusalem, now known as Umariya Elementary School, which he attended for about two years.[21]

1948 Palestine War

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations resolved to partition Palestine into an Arab and Jewish state. Fighting broke out immediately, and the disruption of the citrus-fruit business limited the family's income.[21] In Jaffa there were food shortages, truck bombings, and an Irgun militia mortar bombardment.[22] Melman writes that the al-Banna family had had good relations with the Jewish community.[23] Abu Nidal's brother told Melman that their father had been a friend of Avraham Shapira, a founder of the Jewish defense organization, Hashomer, stating, "He would visit [Shapira] in his home in Petah Tikva, or Shapira riding his horse would visit our home in Jaffa. I also remember how we visited Dr. Weizmann [later first president of Israel] in his home in Rehovot." However, these relationships did not help them weather the war.[23]

Just before Israeli troops took Jaffa in April 1948, the family fled to their house near Majdal, but Israeli troops arrived there too, and the family fled again. This time they went to the Bureij refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, then under Egyptian control. Melman writes that the family spent nine months living in tents, depending on UNRWA for an allowance of oil, rice, and potatoes.[24] The experience had a powerful effect on Abu Nidal.[25]

Move to Nablus and Saudi Arabia

The al-Banna family's commercial experience, and the money they had managed to take with them, meant they could re-establish themselves, Melman writes.[24] Their orange groves were gone, now part of the new state of Israel. The family moved to Nablus in the West Bank, then under Jordanian control.[19] In 1955, Abu Nidal graduated from high school, joined the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party,[26] and began a degree in engineering at Cairo University, but he left after two years without a degree.[27] In 1960, he made his way to Saudi Arabia, where he established himself as a painter and electrician, and worked as a casual laborer for Aramco.[28] His brother told Melman that Abu Nidal would return to Nablus from Saudi Arabia every year to visit his mother. It was during one such visit in 1962 that he met his wife, whose family had also fled Jaffa. Their marriage produced a son and two daughters.[29]

Personality

Abu Nidal was often in poor health, according to Seale, and tended to dress in zip-up jackets and old trousers, drinking whisky every night in his later years. He became, writes Seale, a "master of disguises and subterfuge, trusting no one, lonely and self-protective, [living] like a mole, hidden away from public view".[30] Acquaintances said that he was capable of hard work and had a mind for finances.[31] Salah Khalaf (Abu Iyad), the deputy chief of Fatah who was assassinated by the ANO in 1991, knew him well in the late 1960s when he took Abu Nidal under his wing.[32] He told Seale:

He had been recommended to me as a man of energy and enthusiasm, but he seemed shy when we met. It was only on further acquaintance that I noticed other traits. He was extremely good company, with a sharp tongue and an inclination to dismiss most of humanity as spies and traitors. I rather liked that! I discovered he was very ambitious, perhaps more than his abilities warranted, and also very excitable. He sometimes worked himself up into such a state that he lost all powers of reasoning.[32]

Seale suggests that Abu Nidal's childhood explained his personality, described as chaotic by Abu Iyad and as psychopathic by Issam Sartawi, the late Palestinian heart surgeon.[33][34] His siblings' scorn, the loss of his father, and his mother's removal from the family home when he was seven, followed by the loss of his home and status in the conflict with Israel, created a mental world of plots and counterplots, reflected in his tyrannical leadership of the ANO. Members' wives (the ANO was an all-male group) were not allowed to befriend each other, and Abu Nidal's expected his wife to live in isolation without friends.[35]

Political life

Impex, Black September

In Saudi Arabia, Abu Nidal helped found a small group of young Palestinians who called themselves the Palestine Secret Organization. The activism cost him his job and home: Aramco fired him, and the Saudi government imprisoned, then expelled him in 1967.[26] He returned to Nablus with his wife and family, and joined Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction of the PLO. Working as an odd-job man, he was committed to Palestinian politics but was not particularly active until Israel won the 1967 Six-Day War, capturing the Golan Heights, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Melman writes that "the entrance of the Israel Defense Forces tanks into Nablus was a traumatic experience for him. The conquest aroused him to action."[36]

After moving to Amman, Jordan, he set up a trading company called Impex, which acted as a front for Fatah and served as a meeting place and conduit for funds. This became a hallmark of Abu Nidal's career. ANO-controlled companies controlled made him a rich man by through legitimate business, and functioned as cover for arms deals and mercenary activities.[32]

When Fatah asked him to choose a nom de guerre, he chose Abu Nidal ("father of struggle") after his son, Nidal.[1] Those who knew him at the time said he was a well-organized leader, not a guerrilla; during fighting between the Palestinian fedayeens and King Hussein's troops, he stayed in his office.[37] In 1968, Abu Iyad appointed him as the Fatah representative in Khartoum, Sudan. Later, at Abu Nidal's insistence, he was appointed to the same position in Baghdad in July 1970. He arrived two months before "Black September", when more than 10 days of fighting King Hussein's army drove the Palestinian fedayeens out of Jordan, with the loss of thousands of lives. Abu Nidal's absence from Jordan at a time, Seale writes, when it was clear that King Hussein was about to act against the Palestinians, raised suspicion within the movement that Abu Nidal was interested only in saving himself.[38]

First operation

Shortly after Black September, Abu Nidal began accusing the PLO, over his Voice of Palestine radio station in Iraq, of cowardice for having agreed to a ceasefire with Hussein.[38] During Fatah's Third Congress in Damascus in 1971, he joined Palestinian activist and writer Naji Allush and Abu Daoud (leader of the Black September Organization responsible for the 1972 Munich Massacre) in calling for greater democracy within Fatah and revenge against King Hussein.[39]

In February 1973, Abu Daoud was arrested in Jordan for an attempt on King Hussein's life. This led to Abu Nidal's first operation, using the name Al-Iqab ("the Punishment"). On 5 September 1973, five gunmen entered the Saudi embassy in Paris, took 15 hostages, and threatened to blow up the building if Abu Daoud was not released.[40][41] The gunmen flew to Kuwait two days later on a Syrian Air flight, still holding five hostages, then to Riyadh, threatening to throw the hostages out of the aircraft. They surrendered and released the hostages on 8 September.[42][43] Abu Daoud was released from prison two weeks later; Seale writes that the Kuwaiti government paid King Hussein $12 million for his release.[42]

On the day of the attack, 56 heads of state were meeting in Algiers for the fourth Non-Aligned Movement conference. According to Seale, the Saudi Embassy operation had been commissioned by Iraq's president, Ahmed Hasan al-Bakr, as a distraction because he was jealous that Algeria was hosting the conference. One of the hostage-takers admitted that he had been told to fly the hostages around until the conference was over.[44]

Abu Nidal had carried out the operation without Fatah's permission.[45] Abu Iyad (Arafat's deputy) and Mahmoud Abbas (later President of the Palestinian Authority), flew to Iraq to reason with Abu Nidal and explain that hostage-taking harmed the movement. Abu Iyad told Seale that an Iraqi official at the meeting said, "Why are you attacking Abu Nidal? The operation was ours! We asked him to mount it for us." Abbas was furious and left the meeting with the other PLO delegates. From that point on, the PLO regarded Abu Nidal as under the control of the Iraqi government.[44]

Expulsion from Fatah

Two months later, in November 1973 (just after the Yom Kippur War in October), the ANO hijacked KLM Flight 861, this time using the name Arab Nationalist Youth Organization. Fatah had been discussing convening a peace conference in Geneva and the hijacking was intended to warn them not to go ahead with it. In response, in March or July 1974, Arafat expelled Abu Nidal from Fatah.[46]

In October 1974, Abu Nidal formed the ANO, calling it Fatah: The Revolutionary Council.[47] In November that year, a Fatah court sentenced him to death in absentia for the attempted assassination of Mahmoud Abbas.[48] It is unlikely that Abu Nidal had intended to kill Abbas, and just as unlikely that Fatah wanted to kill Abu Nidal. He was invited to Beirut to discuss the death sentence, and was allowed to leave again, but it was clear that he had become persona non grata.[47] As a result, the Iraqis gave him Fatah's assets in Iraq, including a training camp, farm, newspaper, radio station, passports, overseas scholarships, and $15 million worth of Chinese weapons. He also received Iraq's regular aid to the PLO: around $150,000 a month and a lump sum of $3–5 million.[49]

ANO

Nature of the organization

In addition to Fatah: The Revolutionary Council, the ANO called itself by many names:

- Palestinian National Liberation Movement

- Black June (for actions against Syria)

- Black September (for actions against Jordan)

- Revolutionary Arab Brigades

- Revolutionary Organization of Socialist Muslims

- Egyptian Revolution

- Revolutionary Egypt

- Al-Asifa ("the Storm," a name also used by Fatah)

- Al-Iqab ("the Punishment")

- Arab Nationalist Youth Organization.[2]

The group had up to 500 members[50] chosen from young men in the Palestinian refugee camps and in Lebanon who were promised good pay and help looking after their families.[51] They were sent to training camps in whichever country was hosting the ANO at the time (Syria, Iraq, or Libya), then organized into small cells.[50] Once they had joined the ANO, As'ad AbuKhalil and Michael Fischbach write, they were not allowed to leave again.[52] The group assumed complete control over the membership. One member who spoke to Patrick Seale was told before being sent overseas, "If we say, 'Drink alcohol,' do so. If we say, 'Get married,' find a woman and marry her. If we say, 'Don't have children,' you must obey. If we say, 'Go and kill King Hussein,' you must be ready to sacrifice yourself!"[53]

Recruits were asked to write out their life stories, including names and addresses of family and friends, then sign a paper saying they agreed to execution if they were discovered to have intelligence connections. If the ANO suspected them, they would be asked to rewrite the whole story, without discrepancies.[54] The ANO's newspaper Filastin al-Thawra regularly announced the execution of traitors.[52] Abu Nidal believed that the group had been penetrated by Israeli agents, and there was a sense that Israel may have used the ANO to undermine more moderate Palestinian groups. Terrorism experts regard the view that Abu Nidal himself was such an agent as "far-fetched".[9]

Committee for Revolutionary Justice

There were reports of purges throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Around 600 ANO members were killed in Lebanon and Libya, including 171 in one night in November 1987, when they were lined up, shot, and thrown into a mass grave. Dozens were kidnapped in Syria and killed in the Badawi refugee camp. Most of the decisions to kill, Abu Daoud told Seale, were taken by Abu Nidal "in the middle of the night, after he [had] knocked back a whole bottle of whiskey".[55] The purges led to the defection from the ANO in 1989 of Atef Abu Bakr, head of the ANO's political directorate, who returned to Fatah.[56]

The "Committee for Revolutionary Justice" routinely tortured members until they confessed to disloyalty. Reports of torture included hanging a man naked, whipping him until he was unconscious, reviving him with cold water, then rubbing salt or chili powder into his wounds. A naked prisoner would be forced into a car tyre with his legs and backside in the air, then whipped, wounded, salted, and revived with cold water. A member's testicles might be fried in oil, or melted plastic dripped onto his skin. Between interrogations, prisoners would be tied up in tiny cells. If the cells were full, they might be buried with a pipe in their mouths for air and water; if Abu Nidal wanted them dead, a bullet would be fired down the pipe instead.[57]

Intelligence Directorate

The Intelligence Directorate was formed in 1985 to oversee special operations. It had four subcommittees: the Committee for Special Missions, the Foreign Intelligence Committee, the Counterespionage Committee, and the Lebanon Committee. Led by Abd al-Rahman Isa, the longest-serving member of the ANO—Seale writes that Isa was unshaven and shabby, but charming and persuasive—the directorate maintained 30–40 people overseas who looked after the ANO's arms caches in various countries. It trained staff, arranged passports and visas, and reviewed security at airports and seaports. Members were not allowed to visit each other at home, and no one outside the directorate was supposed to know who was a member.[58] Abu Nidal demoted Isa in 1987, believing he had become too close to other figures within the ANO. Always keen to punish members by humiliating them, he insisted that Isa remain in the Intelligence Directorate, where he had to work for his previous subordinates who were told to treat him with contempt.[59]

Committee for Special Missions

The Committee for Special Missions' job was to choose targets.[60] It had started out as the Military Committee, headed by Naji Abu al-Fawaris, who had led the attack on Heinz Nittel, head of the Israel-Austria Friendship League, who was shot and killed in 1981.[61] In 1982, the committee changed its name to the Committee for Special Missions, headed by Dr. Ghassan al-Ali, who had been born in the West Bank and educated in England, where he obtained a bachelor's degree and a master's degree in chemistry, and married (and later divorced) a British woman.[62] A former ANO member said that Ali favoured "the most extreme and reckless operations".[60]

Operations and relationships

Shlomo Argov

On 3 June 1982, ANO operative Hussein Ghassan Said shot Shlomo Argov, the Israeli ambassador to Britain, once in the head as he left the Dorchester Hotel in London. Said was accompanied by Nawaf al-Rosan, an Iraqi intelligence officer, and Marwan al-Banna, Abu Nidal's cousin. Argov survived, but spent three months in a coma and the rest of his life disabled, until his death in February 2003.[63] The PLO quickly denied responsibility for the attack.[64]

Ariel Sharon, then Israel's defence minister, responded three days later by invading Lebanon, where the PLO was based, a reaction that Seale argues Abu Nidal had intended: the Israeli government had been preparing to invade and Abu Nidal provided a pretext.[65] Der Spiegel put it to him in October 1985 that the assassination of Argov, when he knew Israel wanted to attack the PLO in Lebanon, made him appear to be working for the Israelis, in the view of Yasser Arafat.[66] Abu Nidal replied:[66]

What Arafat says about me doesn't bother me. Not only he, but also a whole list of Arab and world politicians claim that I am an agent of the Zionists or the CIA. Others state that I am a mercenary of the French secret service and of the Soviet KGB. The latest rumor is that I am an agent of Khomeini. During a certain period they said we were spies for the Iraqi regime. Now they say that we are Syrian agents ... Many psychologists and sociologists in the Soviet bloc tried to investigate this man Abu Nidal. They wanted to find a weak point in his character. The result was zero.

Rome and Vienna

Abu Nidal's most infamous operation was the 1985 attack on the Rome and Vienna airports.[67] On 27 December, at 08:15 GMT, four gunmen opened fire on the El Al ticket counter at the Leonardo Da Vinci International Airport in Rome, killing 16 and wounding 99. In the Vienna International Airport a few minutes later, three men threw hand grenades at passengers who were waiting to check into a flight to Tel Aviv, killing 4 and wounding 39.[68][69] The gunmen had been told the people in civilian clothes at the check-in counter were Israeli pilots returning from a training mission.[70]

Austria and Italy had both been involved in trying to arrange peace talks. Sources close to Abu Nidal told Seale that Libyan intelligence had supplied the weapons. The damage to the PLO was enormous, according to Abu Iyad, Arafat's deputy. Most people in the West, and even many Arabs, could not distinguish between the ANO and Fatah, he said. "When such horrible things take place, ordinary people are left thinking that all Palestinians are criminals."[71]

Patrick Seale, Abu Nidal's biographer, wrote of the shootings that their "random cruelty marked them as typical Abu Nidal operations".[72][68]

United States bombing of Libya

On 15 April 1986, the US launched bombing raids from British bases against Tripoli and Benghazi, killing around 100, in retaliation for the bombing of a Berlin nightclub frequented by US service personnel.[73][74] The dead were reported to include Hanna Gaddafi, the adoptive daughter of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi; two of his other children were injured.[75] British journalist Alec Collett, who had been kidnapped in Beirut in March, was hanged after the airstrikes, reportedly by ANO operatives; his remains were found in the Beqaa Valley in November 2009.[76] The bodies of two British teachers, Leigh Douglas and Philip Padfield, and an American, Peter Kilburn, were found in a village near Beirut on 17 April 1986; the Arab Fedayeen Cells, a name linked to Abu Nidal, claimed responsibility.[77] British journalist John McCarthy was kidnapped the same day.[78]

Hindawi affair

On 17 April 1986—the day the teachers' bodies were found and McCarthy was kidnapped—Ann Marie Murphy, a pregnant Irish chambermaid, was discovered in Heathrow airport with a Semtex bomb in the false bottom of one of her bags. She had been about to board an El Al flight from New York to Tel Aviv via London. The bag had been packed by her Jordanian fiancé Nizar Hindawi, who had said he would join her in Israel where they were to be married.[79] According to Melman, Abu Nidal had recommended Hindawi to Syrian intelligence.[80] The bomb had been manufactured by Abu Nidal's technical committee, who had delivered it to Syrian air force intelligence. It was sent to London in a diplomatic bag and given to Hindawi. According to Seale, it was widely believed that the attack was in response to Israel having forced down a jet, two months earlier, carrying Syrian officials to Damascus, which Israel had supposed was carrying senior Palestinians.[81]

Pan Am Flight 73

On 5 September 1986, four ANO gunmen hijacked Pan Am Flight 73 at Karachi Airport on its way from Mumbai to New York, holding 389 passengers and crew for 16 hours in the plane on the tarmac before detonating grenades inside the cabin. Neerja Bhanot, the flight's senior purser, was able to open an emergency door, and most passengers escaped. Twenty died, including Bhanot, and 120 were wounded.[82][83] The London Times reported in March 2004 that Libya had been behind the hijacking.[84]

Relationship with Gaddafi

Abu Nidal began to move his organization out of Syria to Libya in the summer of 1986,[85] arriving there in March 1987. In June that year, the Syrian government expelled him, in part because of the Hindawi affair and Pan Am Flight 73 hijacking.[86] He repeatedly took credit during this period for operations in which he had no involvement, including the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing, 1985 Bradford City stadium fire, and 1986 assassination of Zafer al-Masri, the mayor of Nablus (killed by the PFLP, according to Seale). By publishing a congratulatory note in the ANO's magazine, he also implied that he had been behind the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.[87]

Abu Nidal and Libya's leader, Muammar Gaddafi, allegedly became great friends, each holding what Marie Colvin and Sonya Murad called a "dangerous combination of an inferiority complex mixed with the belief that he was a man of great destiny". The relationship gave Abu Nidal a sponsor and Gaddafi a mercenary.[88] Libya brought out the worst in Abu Nidal. He would not allow even the most senior ANO members to socialize with each other; all meetings had to be reported to him. All passports had to be handed over. No one was allowed to travel without his permission. Ordinary members were not allowed to have telephones; senior members were allowed to make local calls only.[89] His members knew nothing about his daily life, including where he lived. If he wanted to entertain, he would take over the home of another member.[90]

According to Abu Bakr, speaking to Al Hayat in 2002, Abu Nidal said he was behind the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland, on 21 December 1988; a former head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines was later convicted.[91] Abu Nidal reportedly said of Lockerbie, "We do have some involvement in this matter, but if anyone so much as mentions it, I will kill him with my own hands!" Seale writes that the ANO appeared to have no connection to it. One of Abu Nidal's associates told him, "If an American soldier tripped in some corner of the globe, Abu Nidal would instantly claim it as his own work."[85]

Banking with BCCI

In the late 1980s, British intelligence learned that the ANO held accounts with the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) in London.[92] In July 1991, BCCI was closed by banking regulators in six countries after evidence emerged of widespread fraud.[93] Abu Nidal himself was said to have visited London using the name Shakar Farhan; a BCCI branch manager, who passed information about the ANO accounts to MI5, reportedly drove him around several stores in London without realizing who he was.[94] Abu Nidal was using a company called SAS International Trading and Investments in Warsaw as cover for arms deals.[95] The company's transactions included the purchase of riot guns, ostensibly for Syria, then when the British refused an export license to Syria, for an African state; in fact, half the shipment went to the police in East Germany and half to Abu Nidal.[96]

Assassination of Abu Iyad

On 14 January 1991 in Tunis, the night before US forces moved into Kuwait, the ANO assassinated Abu Iyad, head of PLO intelligence, along with Abu al-Hol, Fatah's chief of security, and Fakhri Al Omari, another Fatah aide; all three men were shot in Abu al-Hol's home. The killer, Hamza Abu Zaid, confessed that an ANO operative had hired him. When he shot Abu Iyad, he reportedly shouted, "Let Atef Abu Bakr help you now!", a reference to the senior ANO member who had left the group in 1989, and whom Abu Nidal believed Abu Iyad had planted within the ANO as a spy.[97] Abu Iyad had known that Abu Nidal nursed a hatred of him, in part because he had kept Abu Nidal out of the PLO. However, the real reason for the hatred, Abu Iyad told Seale, was that he had protected Abu Nidal in his early years within the movement. Given his personality, Abu Nidal could not acknowledge that debt. The murder "must therefore be seen as a final settlement of old scores".[98]

Death

After Libyan intelligence operatives were charged with the Lockerbie bombing, Gaddafi tried to distance himself from terrorism. Abu Nidal was expelled from Libya in 1999[99] and, in 2002, he returned to Iraq. The Iraqi government later said he had entered the country using a fake Yemeni passport and false name.[100][101]

On 19 August 2002, the Palestinian newspaper al-Ayyam reported that Abu Nidal had died three days earlier of multiple gunshot wounds at his home in Baghdad, a house the newspaper said was owned by the Mukhabarat, the Iraqi secret service.[88] Two days later, Iraq's chief of intelligence Taher Jalil Habbush handed out photographs of Abu Nidal's body to journalists, along with a medical report that said he had died after a bullet entered his mouth and exited through his skull. Habbush said Iraqi officials had arrived at Abu Nidal's home to arrest him on suspicion of conspiring with foreign governments. After saying he needed a change of clothes, Abu Nidal went into his bedroom and shot himself in the mouth, according to Habbush. He died eight hours later in hospital.[100]

The Janes reported in 2002 that Iraqi intelligence had found classified documents in his home about a US attack on Iraq. When they raided the house, fighting broke out between Abu Nidal's men and Iraqi intelligence. Amid this, Abu Nidal rushed into his bedroom and was killed; Palestinian sources told Janes that he had been shot several times. Janes suggested Saddam Hussein had him killed because he feared Abu Nidal would act against him in the event of an American invasion.[101]

"He was the patriot turned psychopath", David Hirst wrote in The Guardian on the news of his death. "He served only himself, only the warped personal drives that pushed him into hideous crime. He was the ultimate mercenary."[34]

In 2008, Robert Fisk obtained a report written in September 2002, for Saddam Hussein's "presidency intelligence office," by Iraq's "Special Intelligence Unit M4". The report said that the Iraqis had been interrogating Abu Nidal in his home as a suspected spy for Kuwait and Egypt, and indirectly for the United States, and that he had been asked by the Kuwaitis to find links between Iraq and Al-Qaeda. Just before being moved to a more secure location, Abu Nidal asked to be allowed to change his clothing, went into his bedroom and shot himself, the report said.

He was buried on 29 August 2002 in al-Karakh's Islamic cemetery in Baghdad, in a grave marked M7.[14]

See also

Bibliography

- AbuKhalil, As'ad; Fischbach, Michael R. (2005) [2000]. "Abu Nidal – Sabri al-Bana". In Mattar, Philip (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Palestinians. pp. 11-13.

- Adams, James Ring; Frantz, Douglas (1992). A Full Service Bank: How BCCI Stole Billions Around the World. Simon & Schuster.

- Hudson, Rex A. (September 1999). "The Sociology and Psychology of Terrorism: Who Becomes a Terrorist and Why?" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2017.

- Kushner, Harvey W. (2002). "Abu Nidal Organization". Encyclopedia of Terrorism. Sage Publications.

- Melman, Yossi (1987) [1986]. The Master Terrorist: The True Story Behind Abu Nidal. Sidgwick & Jackson.

- Seale, Patrick (1992). Abu Nidal: A Gun for Hire : The Secret Life of the World's Most Notorious Arab Terrorist. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091753276.

- St. John, Ronald Bruce (2011). Libya and the United States: Two Centuries of Strife. University of Pennsylvania Press.

References

- ^ a b AbuKhalil & Fischbach 2005; Melman 1987, p. 53 translates it as "father of the struggle".

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 213

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 99

- ^ a b Randal, Jonathan C. (10 June 1990). "Abu Nidal Battles Dissidents". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014.

- ^ Hudson 1999, p. 97

- ^ "Abu Nidal Organization (ANO)". United States Department of State. June 2004. Archived from the original on 7 February 2005.

- ^ Chamberlin, Paul Thomas (2012). The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order. New York: Oxford University Press, 173.

- ^ Kifner, John (14 September 1986). "On the bloody trail of Sabri al-Banna". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b Partrick, Neil (2015) [1997]. "Abu Nidal", in Martha Crenshaw and John Pimlott (eds.), International Encyclopedia of Terrorism. London: Routledge, 326–327.

- ^ Rashid Khalidi (2020). The Hundred Years' War on Palestine. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-62779-855-6.

- ^ Ilan Pappe (2017). The Biggest Prison on Earth. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-587-5.

- ^ "Abu Nidal - Mossad terrorist". Sott.net. 2 June 2007.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (22 August 2002). "Mystery of Abu Nidal's death deepens". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b Fisk, Robert (25 October 2008). "Abu Nidal, notorious Palestinian mercenary, 'was a US spy'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 45–46; for orange groves, Seale 1992, p. 57

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 45–46; for the military court, image between 122 and 123.

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 45

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 47

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 46

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 58

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 48

- ^ Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 212–213.

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 48–49

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 49

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 49; Seale 1992, p. 59

- ^ a b Hudson 1999, p. 100

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 50

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 50; Seale 1992, p. 64

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 51

- ^ Seale 1992, 56.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 57

- ^ a b c Seale 1992, p. 69

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 3, 51; Seale 1992, p. 57

- ^ a b Hirst, David (20 August 2002). "Abu Nidal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 58–59

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 52

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 513; Seale 1992, p. 70

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 78

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 85–87

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 69; Seale 1992, p. 92

- ^ Kamm, Henry (6 September 1973). "Gunmen Hold 15 Hostages In Saudi Embassy in Paris". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 91

- ^ Kamm, Henry (7 September 1973). "Commandos leave Embassy in Paris". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 92

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 69

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 70; Seale 1992, p. 97–98 (Melman writes that it was March 1974, Seale that it was July).

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 99

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 98

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 100

- ^ a b Kushner 2002, p. 3

- ^ Seale 1992, 6.

- ^ a b AbuKhalil & Fischbach 2005, p. 12

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 21

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 7, 13–18

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 287–289

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 307, 310

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 286–287

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 185–187

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 188

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 183

- ^ Seale 1992, 186.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 182

- ^ Joffe, Lawrence (25 February 2003). "Shlomo Argov". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organisation. Cambridge University Press, 120.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 223-224

- ^ a b Melman 1987, p. 120

- ^ Seale 1992, 246.

- ^ a b Suro, Roberto (13 February 1988). "Palestinian Gets 30 Years for Rome Airport Attack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ "Gunmen kill 16 at two European airports". BBC News. 27 December 1985. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 244

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 245

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 243

- ^ "US launches air strikes on Libya". BBC News. 15 April 1986. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Malinarich, Natalie (13 November 2001). "The Berlin Disco Bombing". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 162

- ^ Pidd, Helen (23 November 2009). "Remains of British journalist Alec Collett found in Lebanon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Kushner 2002, p. 204

- ^ "British journalist McCarthy kidnapped". BBC. 17 April 1986. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 170–174

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 171

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 248

- ^ Melman 1987, p. 190; Seale 1992, p. 252-254

- ^ Rajghatta, Chidanand (17 January 2010). "24 yrs after Pan Am hijack, Neerja Bhanot killer falls to drone". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Swain, Jon (28 March 2004). "Revealed: Gaddafi's air massacre plot". The Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 255

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 257

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 254

- ^ a b Colvin, Marie and Murad, Sonya (25 August 2002). "Executed," The Sunday Times.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 258–259

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 258–260

- ^ "Abu Nidal 'behind Lockerbie bombing'". BBC News. 23 August 2002. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Walsh, Conal (18 January 2004). "What spooks told Old Lady about BCCI". The Observer. Archived from the original on 18 August 2004.

- ^ Fritz, Sarah; Bates, James (11 July 1991). "BCCI Case May Be History's Biggest Bank Fraud Scandal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Adams & Frantz 1992, p. 90

- ^ Adams & Frantz 1992, p. 136

- ^ Adams & Frantz 1992, p. 91

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 32, 34, 312

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 312–313

- ^ St. John 2011, p. 187

- ^ a b Arraf, Jane (21 August 2002). "Iraq details terror leader's death". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 August 2005.

- ^ a b Najib, Mohammed (23 August 2002). "Abu Nidal murder trail leads directly to Iraqi regime", Jane's Information Group.

External links

- Incidents attributed to the Abu Nidal Organization, Global Terrorism Database.

- Abu Nidal

- 1937 births

- 2002 deaths

- 2002 suicides

- Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Iraq Region politicians

- Palestinian mercenaries

- Palestinian Arab nationalists

- Palestinian militants

- Palestinian Muslims

- Palestinian nationalists

- Palestinian refugees

- Palestinian revolutionaries

- People from Jaffa

- Suicides by firearm in Iraq

- Unsolved deaths in Iraq

- People of the Lebanese Civil War

- Arab people in Mandatory Palestine

- Stasi informants