Muhammadu Buhari

Muhammadu Buhari | |

|---|---|

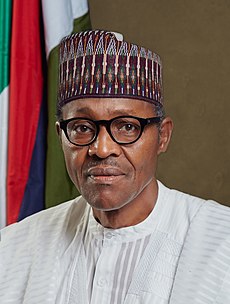

Official portrait, 2015 | |

| 7th and 15th President of Nigeria | |

| In office 29 May 2015 – 29 May 2023 | |

| Vice President | Yemi Osinbajo |

| Preceded by | Goodluck Jonathan |

| Succeeded by | Bola Tinubu |

| In office 31 December 1983 – 27 August 1985 as Military Head of State of Nigeria | |

| Chief of Staff | Tunde Idiagbon |

| Preceded by | Shehu Shagari |

| Succeeded by | Ibrahim Babangida |

| Federal Minister of Petroleum Resources | |

| In office 11 November 2015 – 29 May 2023 | |

| President | Himself |

| Minister of State | Emmanuel Ibe Kachikwu Timipre Sylva |

| Preceded by | Diezani Allison-Madueke |

| Succeeded by | Bola Tinubu |

| In office March 1976 – June 1978 as Federal Commissioner of Petroleum and Natural Resources | |

| Head of State | Olusegun Obasanjo |

| Governor of Borno State | |

| In office 3 February 1976 – 15 March 1976 | |

| Head of State | Murtala Mohammed Olusegun Obasanjo |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Mustapha Amin |

| In office 1 August 1975 – 3 February 1976 as Governor of the North-Eastern State | |

| Head of State | Murtala Mohammed |

| Preceded by | Musa Usman |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 December 1942 Daura, Northern Region, British Nigeria (now in Katsina, Nigeria) |

| Political party | All Progressives Congress (2013–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 10

|

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Nickname | Bubu |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1962–1985 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Nigerian Civil War Chadian–Nigerian War |

Muhammadu Buhari GCFR (ⓘ; born 17 December 1942) is a Nigerian politician and retired Nigerian Army major general who served as the president of Nigeria from 2015 to 2023.[2][3] He also served as the country's military head of state from 31 December 1983 to 27 August 1985, after taking power from the Shehu Shagari civilian government in a military coup d'état.[4][5] The term Buharism is used to describe the authoritarian policies of his military regime.[6][7]

Buhari ran for president of Nigeria on the platform and support of the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP) in 2003 and 2007, and on the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) platform in 2011.[8] In December 2014, he emerged as the presidential candidate of[9] the All Progressives Congress party for the 2015 general election.[10] Buhari won the election, defeating incumbent President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan.[11] This was the first time in the history of Nigeria that an incumbent president lost a re-election bid. He was sworn in on 29 May 2015. In February 2019, Buhari was re-elected, defeating his closest rival, former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, by over 3 million votes.[12][13][14]

Early life

[edit]Muhammadu Buhari was born to a Fulani family[15] on 17 December 1942, in Daura, a town in Katsina State, Nigeria. His father was called Mallam Hardo Adamu, a Fulani chieftain from Dumurkul in Mai'Adua, and his mother, whose name was Zulaihat, had Hausa and Kanuri ancestry.[16][17] He is the twenty-third-(23) child of his father and was named after ninth-century Persian Islamic scholar Muhammad al-Bukhari.[18] Buhari was about four years old when his father died and was thereafter raised by his mother alone. He attended primary school in Daura and Mai'adua, finishing in 1953, Katsina Middle School, and attended Katsina Provincial Secondary School in Katsina State from 1956 to 1961 where he earned his West African School Certificate. Buhari went to the Nigerian Military Training School, Kaduna in 1963.[19][20]

Military career

[edit]In 1962, at the age of 19, Buhari enrolled in the Nigerian Military Training College (NMTC).[21] In February 1964, the college was upgraded to an officer commissioning unit of the Nigerian Army and renamed the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) (prior to 1964, the Nigerian government sent cadets who had completed their NMTC preliminary training to mostly Commonwealth military academies[22][23][24] for officer cadet training).

From 1962 to 1963, Buhari underwent officer cadet training at Mons Officer Cadet School in Aldershot in England.[25] In January 1963, at age 20, Buhari was commissioned a second lieutenant and appointed Platoon Commander of the Second Infantry Battalion in Abeokuta, Nigeria. From November 1963 to January 1964, Buhari attended the Platoon Commanders' Course at the Nigerian Military Training College, Kaduna. In 1964, he facilitated his military training by attending the Mechanical Transport Officer's Course at the Army Mechanical Transport School in Borden, United Kingdom.[26]

From 1965 to 1967, Buhari served as commander of the Second Infantry Battalion and was appointed brigade major, Second Sector, First Infantry Division, April 1967 to July 1967. Following the bloody 1966 Nigerian coup d'état, which resulted in the death of Premier Ahmadu Bello, Lieutenant Buhari, alongside several young officers from Northern Nigeria, took part in the July counter-coup which ousted General Aguiyi Ironsi, replacing him with General Yakubu Gowon.[27]

Civil war

[edit]Buhari was assigned to the 1st Division under the command of Lt. Col Mohammed Shuwa.[28] The division had temporarily moved from Kaduna to Makurdi at the onset of the Nigerian Civil War. The 1st division was divided into sectors and then battalions, [29] with Shuwa assisted by sector commanders Martin Adamu and Sule Apollo, who was later replaced by Theophilus Danjuma. Buhari's initial assignment was as Adjutant and Company Commander 2 battalion unit, Second Sector Infantry of the 1st Division. The 2 battalion was one of the units that participated in the first actions of the war: they started from Gakem near Afikpo and moved towards Ogoja, with support from Gado Nasko's artillery squad.[30] They reached and captured Ogoja within a week, with the intention of advancing through the flanks to Enugu, the rebel capital.[31] Buhari was briefly the 2 battalion's Commander and led the battalion to Afikpo to link with the 3rd Marine Commando and advance towards Enugu through Nkalagu and Abakaliki. However, before the move to Enugu, he was posted to Nsukka as Brigade Major of the 3rd Infantry Brigade under Joshua Gin, who would later become battle fatigued and replaced by Isa Bukar.[32] Buhari stayed with the infantry for a few months as the Nigerian army began to adjust tactics learnt from early battle experiences. Instead of swift advances, the new tactics involved securing and holding on to the lines of communications and using captured towns as training ground to train new recruits brought in from the army depots in Abeokuta and Zaria.[32] In 1968, he was posted to the 4 Sector, also called the Awka sector, which was charged with taking over the capture of Onitsha from Division 2. The sector's operations were within the Awka-Abagana-Onitsha region, which was important to Biafran forces because it was a major source of food supply. It was in the sector that Buhari's group suffered a lot of casualties trying to protect the food supplies route of the rebels along Oji River and Abagana.[33]

After the war

[edit]From 1970 to 1971, Buhari was Brigade Major/Commandant, Thirty-first Infantry Brigade. He then served as the Assistant Adjutant-General, First Infantry Division Headquarters, from 1971 to 1972. He also attended the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington, India, in 1973.[34] From 1974 to 1975 Buhari was acting director of Transport and Supply at the Nigerian Army Corps of Supply and Transport Headquarters.[35]

In the 1975 military coup d'état, Lieutenant Colonel Buhari was among a group of officers that brought General Murtala Mohammed to power. He was later appointed Governor of the North-Eastern State[36][37] from 1 August 1975 to 3 February 1976, to oversee social, economic and political improvements in the state. On 3 February 1976, the North Eastern State was divided into three states Bauchi, Borno and Gongola.[38][39][40] Buhari then became the first Governor of Borno State from 3 February 1976 to 15 March 1976.[41]

In March 1976, following the botched 1976 military coup d'état attempt which led to the assassination of General Murtala Mohammed, his deputy General Olusegun Obasanjo became the military head of state and appointed Colonel Buhari as the Federal Commissioner for Petroleum and Natural Resources (now minister). In 1977, when the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation was created, Buhari was appointed as its chairman, a position he held until 1978.[42]

During his tenure as the Federal Commissioner for Petroleum and Natural Resources, the government invested in pipelines and petroleum storage infrastructures. The government built about 21 petroleum storage depots all over the country from Lagos to Maiduguri and from Calabar to Gusau; the administration constructed a pipeline network that connected Bonny terminal and the Port Harcourt refinery to the depots. Also, the administration signed the contract for the construction of a refinery in Kaduna and an oil pipeline that will connect the Escravos oil terminal to Warri Refinery and the proposed Kaduna refinery.[43]

From 1978 to 1979, he was Military Secretary at the Army Headquarters and was a member of the Supreme Military Council from 1978 to 1979. From 1979 to 1980, at the rank of colonel, Buhari (class of 1980) attended the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in the United States, and gained a master's degree in Strategic Studies.[44][45] Upon completion of the on-campus full-time resident program lasting ten months and the two-year-long, distance learning program, the United States Army War College (USAWC) awards its graduate officers a master's degree in Strategic Studies.[citation needed]

Divisional commands held in the Nigerian Army:

- General Officer Commanding, 4th Infantry Division: August 1980 – January 1981[46]

- General Officer Commanding, 2nd Mechanised Infantry Division: January 1981 – October 1981[47]

- General Officer Commanding, 3rd Armed Division: October 1981 – December 1983

Coup d'état of 1983

[edit]Major-General Buhari was one of the leaders of the military coup of December 1983 that overthrew the Second Nigerian Republic. At the time of the coup plot, Buhari was the General Officer Commanding (GOC), Third Armoured Division of Jos.[48] With the successful execution of the coup by General Buhari, Tunde Idiagbon was appointed Chief of General Staff (the de facto No. 2 in the administration). The coup ended Nigeria's short-lived Second Republic, a period of multi-party democracy revived in 1979, after 13 years of military rule.[49]

According to The New York Times, the officers who took power argued that "a flawed democracy was worse than no democracy at all". Buhari justified the military's seizure of power by castigating the civilian government as hopelessly corrupt and promptly suspended the constitution. Another rationale for the coup was to correct economic decline in Nigeria. In the military's first broadcast after the coup, Sani Abacha linked 'an inept and corrupt leadership'[50] with general economic decline. In Buhari's New Year's Day speech, he too mentioned the corrupt class of the Second Republic but also as the cause of a general decline in morality in society.[50]

Head of State (1983–1985)

[edit]Consolidation of power

[edit]The structure of the new military leadership—the fifth in Nigeria since independence—resembled the last military regime, the Obasanjo/Yaradua administration. The new regime established a Supreme Military Council, a Federal Executive Council and a Council of States.[51] The number of ministries was trimmed to 18, while the administration carried out a retrenchment exercise among the senior ranks of the civil service and police. It retired 17 permanent secretaries and some senior police and naval officers. In addition, the new military administration promulgated new laws to achieve its aim. These laws included the Robbery and Firearms (Special Provisions) Decree for the prosecution of armed robbery cases, and the State Security (Detention of Person) Decree, which gave powers to the military to detain individuals suspected of jeopardizing state security or causing economic adversity.[52] Other decrees included the Civil Service Commission and Public Offenders Decree, which constituted the legal and administrative basis to conduct a purge in the civil service.[52]

According to Decree Number 2 of 1984, the state security and the chief of staff were given the power to detain, without charges, individuals deemed to be a security risk to the state for up to three months.[53] Strikes and popular demonstrations were banned and Nigeria's security agency, the National Security Organization (NSO) was entrusted with unprecedented powers. The NSO played a wide role in the cracking down of public dissent by intimidating, harassing and jailing individuals who broke the interdiction on strikes. By October 1984, about 200,000 civil servants were retrenched.[54] Buhari mounted an offensive against entrenched interests. In 20 months as Head of State, about 500 politicians, officials and businessmen were jailed for corruption during his stewardship.[55][56] Detainees were released after releasing sums to the government and agreeing to meet certain conditions. The regime also jailed its critics, including Fela Kuti.[57] He was arrested on 4 September 1984 at the airport as he was about to embark on an American tour. Amnesty International described the charges brought against him for illegally exporting foreign currency as "spurious". Using the wide powers bestowed upon it by Decree Number 2, the government sentenced Fela to five years in prison. He was released after 18 months,[57] when the Buhari regime was overthrown.

In 1984, Buhari passed Decree Number 4, the Protection Against False Accusations Decree,[58] a wide-ranging repressive press law. Section 1 of the law provided that "Any person who publishes in any form, whether written or otherwise, any message, rumour, report or statement [...] which is false in any material particular or which brings or is calculated to bring the Federal Military Government or the Government of a state or public officer to ridicule or disrepute, shall be guilty of an offense under this Decree".[59] The law further stated that offending journalists and publishers will be tried by an open military tribunal, whose ruling would be final and unappealable in any court and those found guilty would be eligible for a fine not less than 10,000 naira and a jail sentence of up to two years.[60]

Economics

[edit]

In order to reform the economy, as Head of State, Buhari started to rebuild the nation's social-political and economic systems, along the realities of Nigeria's austere economic conditions.[61] The rebuilding included removing or cutting back the excesses in national expenditure, obliterating or removing completely, corruption from the nation's social ethics, shifting from mainly public sector employment to self-employment. Buhari also encouraged import substitution industrialisation based to a great extent on the use of local materials.[61] However, tightening of imports led to reduction in raw materials for industries causing many industries to operate below capacity,[62] reduction of workers and in some cases business closure.[55]

Buhari broke ties with the International Monetary Fund, when the fund asked the government to devalue the naira by 60%. However, the reforms that Buhari instigated on his own were as or more rigorous as those required by the IMF.[63][64]

On 7 May 1984, Buhari announced the country's 1984 National Budget. The budget came with a series of complementary measures:

- A temporary ban on recruiting federal public sector workers

- Raising of interest rates

- Halting capital projects

- Prohibition of borrowing by state governments

- 15 percent cut from Shagari's 1983 Budget

- Realignment of import duties

- Reducing the balance of payment deficit by cutting imports

- It also gave priority to the importation of raw materials and spare parts that were needed for agriculture and industry.

Other economic measures by Buhari took the form of counter trade, currency change, price reduction of goods and services. His economic policies did not earn him the legitimacy of the masses due to the rise in inflation and the use of military might to continue to push many policies blamed for the rise in food prices.[65]

Mass social mobilization

[edit]One of the most enduring legacies of the Buhari government has been the War Against Indiscipline (WAI). Launched on 20 March 1984, the policy tried to address the perceived lack of public morality and civic responsibility of Nigerian society. Unruly Nigerians were ordered to form neat queues at bus stops, under the eyes of whip-wielding soldiers. Civil servants[66] who failed to show up on time at work were humiliated and forced to do "frog jumps". Minor offences carried long sentences. Any student over the age of 17 caught cheating on an exam would get 21 years in prison. Counterfeiting and arson could lead to the death penalty.[67]

Buhari's administration enacted three decrees to investigate corruption and control foreign exchange. The Banking (Freezing of Accounts) Decree of 1984, allotted to the Federal Military Government the power to freeze bank accounts of persons suspected to have committed fraud. The Recovery of Public Property (Special Military Tribunals) Decree permitted the government to investigate the assets of public officials linked with corruption and constitute a military tribunal to try such persons. The Exchange Control (Anti-Sabotage) Decree stated penalties for violators of foreign exchange laws.[68]

Decree 20 on illegal ship bunkering and drug trafficking was another example of Buhari's tough approach to crime.[69] Section 3 (2) (K) provided that "any person who, without lawful authority deals in, sells, smokes or inhales the drug known as cocaine or other similar drugs, shall be guilty under section 6 (3) (K) of an offence and liable on conviction to suffer death sentence by firing squad." In the case of Bernard Ogedengebe, the Decree was applied retroactively.[70] He was executed even if at the time of his arrest the crime did not mandate the capital punishment, but had carried a sentence of six months imprisonment.[70] In another prominent case of April 1985, six Nigerians were condemned to death under the same decree: Sidikatu Tairi, Sola Oguntayo, Oladele Omosebi, Lasunkanmi Awolola, Jimi Adebayo and Gladys Iyamah.[71]

In 1985, prompted by economic uncertainties and a rising crime rate, the government of Buhari opened the borders (closed since April 1984) with Benin, Niger, Chad and Cameroon to speed up the expulsion of 700,000 illegal foreigners and illegal migrant workers.[72] Buhari is today known for this crisis; there even is a famine in the east of Niger that have been named "El Buhari".[73] His regime drew criticism from many, including Nigeria's first Nobel Prize winner Wole Soyinka, who, in 2007, wrote a piece called "The Crimes of Buhari"[74] which outlined many of the abuses conducted under his military rule.

Ahead of the 2015 general election, Buhari responded to his human rights criticism by saying that if elected, he would follow the rule of law, and that there would be access to justice for all Nigerians and respect for fundamental human rights of Nigerians.[75]

Coup d'état of 1985

[edit]In August 1985, Major General Buhari was overthrown in a coup led by General Ibrahim Babangida and other members of the ruling Supreme Military Council (SMC).[76] Babangida brought many of Buhari's most vocal critics into his administration, including Fela Kuti's brother Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, a doctor who had led a strike against Buhari to protest declining health care services. Buhari was then detained in Benin City until 1988.[77]

Pre-presidency (1985–2015)

[edit]Detention

[edit]Buhari spent three years of detention in a small guarded bungalow in Benin.[78] He had access to television that showed two channels and members of his family were allowed to visit him on the authorization of Babangida.[79]

Civilian life

[edit]In December 1988, after his mother's death he was released and retired to his residence in Daura. While in detention, his farm was managed by his relatives. He divorced his first wife in 1988 and married Aisha Halilu.[1] In Katsina, he became the pioneer chairman of Katsina Foundation that was founded to encourage social and economic development in Katsina State.[citation needed]

Buhari served as the Chairman of the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF), a body created by the government of General Sani Abacha, and funded from the revenue generated by the increase in price of petroleum products, to pursue developmental projects around the country. A 1998 report in New African praised the PTF under Buhari for its transparency, calling it a rare "success story".[80]

Presidential campaigns and elections

[edit]

2003 presidential election

In 2003, Buhari ran for the office of the president[81] as the candidate of the All Nigeria People's Party (ANPP). He was defeated by the People's Democratic Party incumbent, President Olusẹgun Ọbasanjọ, by more than 11 million votes.[82]

2007 presidential election

[edit]On 18 December 2006, Buhari was nominated as the consensus candidate of the All Nigeria People's Party. His main challenger in the April 2007 polls was the ruling PDP candidate, Umaru Yar'Adua, who hailed from the same home state of Katsina. Buhari officially took 18% of the vote to Yar'Adua's 70%, but Buhari rejected these results.[83] After Yar'Adua took office, he called for a government of national unity to bring on board aggrieved opposition members. The ANPP joined the government with appointment of its national chairman as a member of Yar'Adua's cabinet, but Buhari denounced this agreement.[84]

2011 presidential election

[edit]In March 2010, Buhari left the ANPP for the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), a party he had helped to found. He said that he had supported foundation of the CPC "as a solution to the debilitating, ethical and ideological conflicts in my former party the ANPP".[85]

Buhari was the CPC presidential candidate in the 2011 election, running against incumbent President Goodluck Jonathan of the People's Democratic Party (PDP), Mallam Nuhu Ribadu of Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), and Ibrahim Shekarau of ANPP. They were the major contenders among 20 candidates.[86] Buhari campaigned on an anti-corruption platform and pledged to remove immunity protections from government officials. He also gave support to enforcement of Sharia law in Nigeria's northern states, which had previously caused him political difficulties among Christian voters in the country's south.[55]

The elections were marred by widespread sectarian violence, which claimed the lives of 800 people across the country, as Buhari's supporters attacked Christian settlements in the country's central region.[87] The three-day uprising was blamed in part on Buhari's inflammatory comments.[87] In spite of assurances from Human Rights Watch, which had judged the elections "among the fairest in Nigeria's history", Buhari claimed that the vote was flawed and warned[87] that "If what happened in 2011 should again happen in 2015, by the grace of God, the dog and the baboon would all be soaked in blood".[88][89]

Buhari remained a "folk hero" to some for his vocal opposition to corruption.[90] He won 12,214,853 votes, coming in second to Jonathan, who polled 22,495,187 votes and was declared the winner.[91]

2015 presidential election

[edit]

Buhari ran in the 2015 presidential election as a candidate of the All Progressives Congress party. His platform was built around his image as a staunch anti-corruption fighter and his incorruptible and honest reputation, but he said he would not probe past corrupt leaders and would give officials who stole in the past amnesty if they repented.[92]

In the runup to the 2015 election, Jonathan's campaign asked that Buhari be disqualified from the election, claiming that he was in breach of the Constitution.[93] According to the fundamental document, in order to qualify for election to the office of the president, a person must be "educated up to at least School certificate level or its equivalent". Buhari failed to submit any such evidence, claiming that he lost the original copies of his diplomas when his house was raided following his overthrow from power in 1985.[94]

In May 2014, in the wake of the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping, Buhari strongly denounced the Boko Haram insurgency. He "urged Nigerians to put aside religion, politics and all other divisions to crush the insurgency he said is fanned by mindless bigots masquerading as Muslims".[95] In July 2014, Buhari escaped a bomb attack on his life by Boko Haram in Kaduna, 82 people were killed.[96] In December 2014, Buhari pledged to enhance security in Nigeria if elected president.[97] After this announcement, Buhari's approval ratings skyrocketed, largely due to Jonathan's apparent inability to fight Boko Haram. Buhari made internal security and wiping out the militant group one of the key pillars of his campaign. In January 2015, the insurgent group "The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta" (MEND) endorsed Buhari.[98]

In February 2015, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo quit the ruling PDP party and endorsed Buhari.[99]

On 31 March, Jonathan called Buhari to concede and congratulate him on his election as president.[100] Buhari was sworn in on 29 May 2015 in a ceremony attended by at least 23 heads of state and government.[101]

Second inauguration

[edit]The second inauguration of Buhari as the 15th president of Nigeria, and 4th president in the fourth Nigerian Republic took place on Wednesday, 29 May 2019, following the 2019 Nigerian presidential election and marking the start of the second and final four-year term of Muhammadu Buhari as president and Yemi Osinbajo as vice president.[102] It was the 8th presidential inauguration in Nigeria, and 6th in the fourth republic.[103][104]

The official swearing-in ceremony took place at Eagle Square in Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory. Acting Chief Justice Tanko Muhammad administered the oath of office taken by President Buhari and Vice President Yemi Osinbajo. The traditional inaugural speech was not delivered.[104] Former Nigerian heads of state General Yakubu Gowon, General Ibrahim Babangida, Interim President Ernest Shonekan, General Abdulsalami Abubakar, General Olusegun Obasanjo and President Goodluck Jonathan were in attendance.

Presidency (2015–2023)

[edit]

The economy has averaged a growth rate of 0.9% since the administration's first term, unemployment is at an all-time high of 23%, and millions entered poverty.[105] Since 2015, Buhari has lost supporters due to his perceived un-energetic personality and contemplative decision making.[106]

Cabinet

[edit]Buhari's key advisers include: his nephew Mamman Daura, businessman Ismaila Isa Funtua, political operator Baba Gana Kingibe, Abba Kyari the Chief of Staff to the President; and from the late stages of his first term, Boss Mustapha the Secretary to the Government of the Federation.[107] Empowering his kitchen cabinet after his second inauguration, Buhari has stated his preference for cabinet members seeking meetings or consultation to direct such requests through the chief of staff or through the government secretary.[107]

Since the Fourth Republic, ministerial positions are legally required to be composed of a federal ethno-demographic character with a minister representing each state of the federation. A result of this has created the outcome of political considerations as an important factor in nominating ministers as local party officials lacking in merit jostle for cabinet positions.[107] Nomination into Buhari's cabinet has been influenced by those political considerations and also closeness to the president and his inner cabinet.[107]

In August 2019, the president named his cabinet of predominantly male members with an average years of 60 and dominated by political actors or those close to the president.[108] The cabinet include two wealthy former governors from the Niger Delta, Timipre Sylva and Godswill Akpabio who were originally members of the opposition party PDP and fourteen retained ministers some of whom critics alleged had performed poorly or having a close relationship with a corrupt past Head of State.[108]

Health

[edit]In May 2016, Buhari cancelled a two-day visit to Lagos to inaugurate projects in the state but he was represented by the Vice-president Yemi Osinbajo after citing an "ear infection" suspected to be Ménière's disease.[109] On 6 June, Buhari travelled to the United Kingdom to seek medical attention.[110][111] This happened days after the Presidential Spokesman Femi Adesina was quoted as saying Buhari was "as fit as fiddle" and "hale and hearty", to much discontent and criticism from political analysts and followers.[112][113][114] In February 2017, following what were described as "routine medical check-ups" in the UK,[115] Buhari asked parliament to extend his medical leave to await test results.[116] His office did not give any further details on his health condition nor the expected date of his return.[117] On 8 February, President Buhari personally signed a letter addressed to the President of the Senate of Nigeria alerting him of a further extension to his annual leave, leaving his vice president in charge.[118][119][120] Following an absence of 51 days from office, President Buhari returned to Nigeria. He arrived at Kaduna Airport in the morning of 10 March.[121][122][123] Although information was limited during his stay in London, he was pictured on 9 March meeting the most senior cleric of the world Anglican congregation, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby.[124][125] Vice President Yemi Osibanjo remained in charge as acting president, while the President continued to recover in Abuja.[126] The President has missed major official and public appearances just two months following his return to office from England. Most recently he was absent from the Federal Executive Council (FEC) meeting, the worker's day event held at the Eagle Square in Abuja on May Day 2017.[127][128][129] Speculations about the President's health circulated in the public sphere in the days following President Buhari's wishes to "work from home".[130] Some prominent Nigerian figures urged the President to take a long-term medical leave,[131][132] citing his failure to make any public appearances over a two-week period.[133][134]

President Buhari again left Nigeria for a reported health check-up in London on 7 May 2017.[135] President Buhari returned to Nigeria from his medical leave in the United Kingdom 104 days after leaving, on 19 August 2017.[136][137] On 8 May, Buhari left Nigeria to London for medical check up, upon arrival from USA; and he returned on Friday 11 May 2018.[138]

Economy

[edit]Buhari was an attractive choice to many Nigerians because of a perceived incorruptible character.[139] Once in power, Buhari who had earlier mobilized supporters in three previous elections was slow to manifest his intention to solve problems he mentioned during his campaign. Determination to initiate his domestic policy agenda like naming of cabinet officials took six months,[139] while the passage of the 2016 and 2017 budgets were delayed by infighting.

In Buhari's first year in office, Nigeria suffered a decline in commodity prices which triggered an economic recession.[140] To source funds to close shortfall in revenue and fund an expansionary capital budget, Buhari traveled to 20 countries seeking loans.[141] Thereby, expansionary budget allocation to finance infrastructure was pushed back to a further date.[142]

In the first year of the administration, Naira, the currency of Nigeria depreciated in the black market leading to a gulf between the official exchange rate and the black-market rate.[143] A resulting shortage in foreign exchange hit various businesses including petroleum marketers. However, the gulf between the official rates and the black market rates opened up the opportunity for well connected individuals to engage in arbitrage, making a mockery of the president's anti-corruption image.[144] In May 2016, the government announced a rise in the official pump price of petroleum to curtail shortfall in the commodity as a result of foreign exchange shortages.[145]

In 2016, the country's economy declined by 1.6% and in 2017 per capita economic growth is projected to be negligible. Buhari's first tenure as head of state coincided with a decline in oil prices similar to his second stint but his administration has not shown dedicated effort to diversify sources of government spending.[144] The 2018 budget signaled an expansionary fiscal policy with funds dedicated to infrastructural projects such as strategic roads, bridges and power plants.[146]

Since an upturn in economic growth from the decline of 2016, a slow pace of recovery has the country behind many of its continental neighbors in GDP growth. Unemployment levels remain high and any effort to increase non-oil revenues has not improved while government deficit spending include a significant portion of its yearly budget dedicated to service debts.[147]

Buhari with the support of the Central Bank chief initiated policies to improve agriculture production through lobbying private banks to lend to the sector and restriction of foreign exchange at official rates for importation of food product that are grown locally. In his second term, the budget minister, Udo Udoma and trade minister, Enemalah both of whom favored liberalisation were not returned.[107]

The government continued to operate flexible exchange rates into the second term of the administration despite critics alluding to the exchange rate regime of being susceptible to arbitrage abuses and round tripping by cronies of the government.[147]

Social welfare

[edit]In 2016, Buhari launched the National Social Investment Program, a national social welfare program.[148] The Program was created to ensure a more equitable distribution of resources to vulnerable populations, including children, youth, and women. There are four programs which address poverty, unemployment and help increase economic development:[149]

- The N-Power program provides young Nigerians with job training and education, as well as a monthly stipend of 30,000 Nigerian naira (US$83.33).

- Npower is a social investment scheme initiated by President Muhammadu Buhari on 8 June 2016 in an attempt to boost the youths employment rate. The scheme was established as a core component of the National Social Investment program to cushion the skill acquisition training and capacity building in the beneficiaries.

- The Conditional Cash Transfer Program (CCTP) directly supports the most vulnerable by providing cash to those in the lowest income group, helping reduce poverty, improve nutrition and self-sustainability, and supporting development through increased consumption.[150]

- The Government Enterprise and Empowerment Program (GEEP) is a micro-lending entrepreneurship program targeting farmers, petty traders and market women with a focus. This program provides no-cost loans to its beneficiaries, helping reduce the start-up costs of business ventures in Nigeria. The programs include: TraderMoni, MarketMoni and FarmerMoni.

- The National Home Grown School Feeding Program (NHGSF) is attempting to increase school enrollment by providing free meals to schoolchildren, particularly those in poor and food-insecure regions. The program works with local farmers and empowers women as cooks, building the community and sustaining economic growth from farm to table.

The program was previously co-ordinated from the office of Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, until 2019, when the program was moved to the new Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development under Sadiya Umar Farouq. In his 2019 Independence Day Speech, the President attributed the movement to the need to have the programmes institutionalized.[151]

Anti-corruption

[edit]

The $2 billion arms deal was exposed following the interim report of Buhari's investigations committee on arms procurement under the Goodluck Jonathan administration. The committee report showed extra-budgetary spending to the tune of N643.8 billion and additional spending of about $2.2 billion in the foreign currency component under Goodluck Jonathan's watch. Preliminary investigation suggested that about $2 billion may have been disbursed for the procurement of arms to fight against the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. The investigative report indicated that a total sum of $2.2 billion was inexplicably disbursed into the office of the National Security Adviser in the procurement of arms to fight against insurgency, but was not spent for the purpose for which the money was disbursed. Investigations on this illegal deal led to the arrest of Sambo Dasuki, the former National Security Adviser who later mentioned prominent Nigerians involved in the deal. Those who were mentioned and arrested includes Raymond Dokpesi, the Chair Emeritus of DAAR Communications Plc, Attahiru Bafarawa, the former Governor of Sokoto State, and Bashir Yuguda, the former Minister of State for Finance, Azubuike Ihejirika, the Chief of Army Staff, Adesola Nunayon Amosu, the former Chief of the Air Staff, Alex Badeh and several other politicians were mentioned.[152]

On 21 December 2016, the government's Federal Ministry of Finance announced a whistle-blowing policy with a 2.5%-5% reward.[153] The aim is to obtain relevant data or information regarding: the violation of financial regulations, the mismanagement of public funds and assets, financial malpractice, fraud, and theft.[154]

In May 2018, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Nigeria's anti-corruption agency, announced that 603 Nigerian figures had been convicted on corruption charges since Buhari took office in 2015.[155] The EFCC also announced that for the first time in Nigeria's history, judges and top military officers including retired service chiefs are being prosecuted for corruption.[155] The successful prosecutions were also credited to Buhari's EFCC head Ibrahim Magu.[155] Under Buhari, Chief Justice of the Nigerian Court Walter Onnoghen was convicted by the Code of Conduct Tribunal on 18 April 2019, for false assets declaration.[156] In December 2019, Mohammed Bello Adoke, the former Attorney General of the Federation, was extradited to Nigeria to stand trial on corruption charges.[157] In January 2020, however, Transparency International still gave Nigeria a low performance in its corruption perception index.[158][159]

In July 2020, Ibrahim Magu the EFCC chairman was arrested by the Department of State Services (DSS) over damaging security reports concerning his activities as the Buhari administration's leading anti-corruption figure and alleged financial irregularities, he was later replaced by Mohammed Umar.[160][161][162][163] In December 2020, Former Pension Reform Taskforce head Abdulrasheed Maina, who was arrested in the neighboring country of Niger after jumping bail, appeared in an Abuja court on a 12-count charge of fraud and money laundering.[164] Ali Ndume, a senator representing Borno South, was arrested after jumping bail as well.[165]

Security issues

[edit]Niger Delta

[edit]Nigeria has the second-largest reserves of crude oil in Africa, reserves largely found in the Niger Delta region of the country. Years of oil production have resulted negative impact on farming and fishery by oil spillage.[166] The government initiated Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP) to help clean up Ogoniland while other state governors within the region want a similar setup. HYPREP was initiated in 2005 but has been slow to commence remediation works in Ogoniland.[166]

Nonetheless, there are still intermittent attacks on oil facilities by groups such as the Niger Delta Avengers. This has significantly affected oil production leading to cuts in exports and government revenue.[167] The Avengers are waging conflict for greater economic and political autonomy.[168]

Shia Muslims

[edit]The Islamic Movement of Nigeria led by Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky is one of the country's leading organization of Shia Muslims. Nigeria's Muslim population is mainly Sunni while the Shia population have gone through sporadic persecution by governments.[169] After the Islamic movement was accused of an attack against Chief of Army Staff Tukur Buratai in December 2015, Zakzaky's base was shelled causing hundreds of fatalities while Zakzaky was arrested.[169] Zakzaky was held for almost six years, aside from a three-day medical trip to India, until being acquitted and released in July 2021.[170]

Biafra separatists

[edit]A separatist group, the Indigenous People of Biafra and led by Nnamdi Kanu became high profile in 2015 for advocating independence for a separate nation of Biafra.[169] A breakaway Biafra republic was briefly formed during Nigeria's Civil War. In October 2015, Kanu was arrested on allegation of treason, his arrest was followed by protests against his detention across many Southeastern states.[169] Kanu later jumped bail and fled abroad to help lead the low-level insurgency in Southeastern Nigeria before being arrested by Interpol and brought back to Nigeria.[171]

Boko Haram

[edit]Since 2015, the fight against the extremists has taken a new dimension, internally the groups have splintered into the traditional Boko Haram sect controlled by Abubakar Shekau and the Islamic State in West Africa Province controlled by Abu Musab al-Barnawi.[172] Other groups supported by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb such as Ansaru, who were driven from Mali due to the French-led Operation Serval have surfaced and co-operated with Boko Haram despite being its rival.[173] This was mostly out of necessity, as the two factions could not risk to weaken themselves by fighting each other.[174] In February 2020, over two hundred and fifty Ansaru members were killed in a police raid in Birnin Gwari.[175]

In October 2016, the government negotiated a deal with the terrorist group, Boko Haram which secured the release of 21 Chibok girls.[176] By December 2016, the government had recovered much of the territories previously held by Boko Haram and after the capture of Sambisa Forest, Buhari announced that Boko Haram has been technically defeated. The insurgency displaced about 2 million people from their homes and the recapture of the towns now present humanitarian challenges in health, education and nutrition.[177] On 6 May 2017, Buhari's government secured a further release of 82 out of 276 girls kidnapped in 2014, in exchange of five Boko Haram leaders.[178] On 7 May 2017, President Buhari met with the 82 released Chibok girls, before departing to London, UK, for a follow-up treatment for an undisclosed illness.[179]

Shekau committed suicide after his grouping was encircled by ISWAP rivals in May 2021. In the months following, hundreds of "repentant" terrorists surrendered to the government, many of whom were allegedly loyal to Shekau.[180]

Herder–farmer violence

[edit]The Middle Belt region of Nigeria has been vulnerable to clashes between farmers and cattle herders, two groups trying to secure arable land for grazing or farming and access to water.[169] The intensity and politicization of the conflict along ethnic and religious divide increased during the administration of Buhari as instances of conflicts flared in parts of Southern Nigeria.[169] About 300 civilians were killed in a village in Benue State, Middle-Belt of the country and about 40 civilians were killed in Enugu in Southeastern Nigeria.[169] The violence has displaced upwards of 250,000 villagers[181] who migrate to cities ill-prepared to handle the influx of migrants. The conflict between farmers many of whom are largely Christians and herders who are predominantly Muslims has stoked religious tension not helped when the president sent in military troops disarm ethnic Christian militias while critics allege of his lukewarm towards armed cattle herders.[181]

The administration's effort to solve the conflict led to the National Livestock Transformation Plan to modernise cattle grazing and stabilize the Middle Belt region.[181] In 2017, RUGA, an acronym for Rural Grazing Area but also a word meaning settlement in Fulani was a proposed solution that came from deliberations of the transformation plan.[181] RUGA was to set aside grazing areas for herders as they migrate south, however, many Southern states opposed any involuntary acquisition of land for RUGA and the plan was suspended[181]

Banditry in Northern Nigeria

[edit]Since 2015, the Buhari Administration has suffered with an increased spate of banditry-related activities in Northern Nigeria.[182] The Abuja-Kaduna highway has been termed the "highway of kidnapping", due to the rampant atrocities committed by bandits.[183] In February 2020, the Northern Elders Forum, a socio-political organisation, said the administration has failed Nigerians in terms of security.[184]

By July 2021, about 45 people a day were kidnapped, largely by bandits for ransom.[185] Other bandits focused on stealing cattle, camels, and other livestock while some groups attacked and seized control of entire villages and wider territories. The banditry lead to fears of collaboration between bandits and Northeastern terrorists with those fears being confirmed in August 2021 when the Nigeria Immigration Service reported that large groups of Zamfara-based bandits were traveling to Borno State for training from Boko Haram.[186]

National issues

[edit]Ruga policy

[edit]The Buhari administration introduced the controversial Ruga policy (human settlement policy), aimed at resolving the conflict between nomadic Fulani herdsmen and sedentary farmers. The policy, which is currently suspended, would "create reserved communities where herders will live, grow and tend their cattle, produce milk and undertake other activities associated with the cattle business without having to move around in search of grazing land for their cows."[187]

Alleged militarization

[edit]Buhari has faced a lot of criticism in office. In 2019 his government came under widespread criticism over the unfair treatment[188] of US-based Social Activist Sowore during his trial, despite the court granting him bail.[189] This move was largely condemned, with Sowore himself stating that Buhari had violated his civic space.[190] In December 2019, Nigeria's Newspaper Giants: PUNCH stated that henceforth they would addressed Buhari's administration as a "regime"[191] and subsequently address him as "General Buhari"[191] as his military-like administration was a far cry from democracy. They insisted that he was a 'military dictator',[192] a move that was greeted with mixed receptions on social media.[193]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria, Buhari established a Presidential Task Force for the control of the virus in the country.[194] On 23 March, Buhari's chief of staff Abba Kyari tested positive for COVID-19 sparking fears that Buhari may have been infected, it was later revealed that Buhari tested negative.[195] On 30 March, Buhari announced a two-week lockdown on major cities Abuja, Lagos and Ogun.[196]

On 14 October, the presidential task force on COVID-19 warned about a potential second wave "if the guidelines and protocols are not adhered to strictly".[197]

End SARS protests

[edit]In October 2020, protests against alleged police brutality of a special police unit of the Nigerian Police Force the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) erupted in Lagos and other major cities. The End SARS movement with no centralised leadership beyond the small assembly that organized the initial protests, share similarities with the 2012 Occupy movement.[198]

On 12 October, a day after demonstrators declared their demands Buhari announced the disbandment of SARS and promised "extensive police reforms".[199] Since independence in 1960, the Nigerian Police Force has been at the forefront of tackling organised crime in Nigeria with the recent spate of banditry, cultism, drug trafficking, fraud and kidnapping drastically affecting its personnel capacity,[200] leaving a vacuum for SARS members to exploit and commit extrajudicial killings.[201]

On 13 October Mohammed Adamu the Inspector General of Police announced the creation of a new unit the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) to take over the duties of SARS.[202] This move did not satisfy most demonstrators, who expected a substantial overhaul of the police structure.[203] On 14 October, the demonstrations continued with at least ten protestors being killed, and violent clashes occurring between pro-SARS and anti-SARS protesters with the elite Presidential Guard Brigade intervening in the federal capital.[204]

On 12 June 2021, Buhari ordered a nationwide deployment of members of the Nigerian Police Force and that of the Nigerian Army, to prevent planned anti-government protests. The government said it was to forestall the breakdown of law and order that became the norm during the October 2020 EndSARS protests.[205]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Buhari described the military crackdown by the Myanmar Army and police on Rohingya Muslims as ethnic cleansing and warned of a disaster like the Rwandan genocide.[206]

Nigeria and South Africa between them share about 50% of Africa's economic output but both countries macroeconomic structure is hampered by high poverty rates, youth unemployment and decline in capital investment.[207] About 600,000 Nigerians have emigrated to South Africa to seek out better economic opportunities and like in Nigeria, it is an economy struggling with its own high unemployment rates. Tensions between migrants and the local populace have occasionally flared up, in 2008, 2015 and in 2019. The last resulted in the violence between migrants including Nigerians and black South Africans. The leaders of both countries met in early October 2019, to discuss measures to improve the relationship between both countries which has been affected not only by anti-migrant violence in South Africa both issues about profit repatriation by South African firms operating in Nigeria.[citation needed]

Buhari is the first president to call for a global treaty to end violence against women and girls.[208]

Post-presidency (2023–present)

[edit]Buhari handed over power peacefully to his successor Bola Tinubu on 29 May 2023 at 10AM (WAT) at an inauguration ceremony in Eagle Square, Federal Capital Territory. He left the seat of power in Abuja immediately after the handover ceremony and in keeping with the tradition of past heads of state and presidents returned to his home state of Katsina where he was received by state and traditional dignitaries before evidently retiring to his farm and family seat in Daura.[209]

Controversies

[edit]US$2.8 billion NNPC scandal

[edit]During his tenure as Federal Commissioner of Petroleum and Natural Resources, US$2.8 billion allegedly went missing from the accounts of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) in Midlands Bank in the United Kingdom. General Ibrahim Babangida later allegedly accused Buhari of being responsible for this fraud.[210][211][212]

However, in the conclusion of the Crude Oil Sales Tribunal of Inquiry headed by Justice Ayo Irikefe to investigate allegations of 2.8 billion Dollars misappropriation from the NNPC account, the tribunal found no truth in the allegations even though it noticed some lapses in the NNPC accounts.[213]

Chadian military affair

[edit]In 1983, when Chadian forces invaded Nigeria in the Borno State, Buhari used the forces under his command to chase them out of the country, crossing into Chadian territory in spite of an order given by President Shagari to withdraw.[214] This 1983 Chadian military affair led to more than 100 victims and "prisoners of war".[214]

Umaru Dikko affair

[edit]The Umaru Dikko Affair was another defining moment in Buhari's military government. Umaru Dikko, a former Minister of Transportation under the previous civilian administration of President Shagari who fled the country shortly after the coup, was accused of embezzling $1 billion in oil profits. With the help of an alleged former Mossad agent, the NSO traced him to London, where operatives from Nigeria and Israel drugged and kidnapped him. They placed him in a plastic bag, which was subsequently hidden inside a crate labelled as "Diplomatic Baggage". The purpose of this secret operation was to ship Dikko off to Nigeria on an empty Nigerian Airways Boeing 707, to stand trial for embezzlement. The plot was foiled by British airport officers.[215]

53 suitcases saga

[edit]Buhari's administration was embroiled in a scandal concerning the fate of 53 suitcases with unknown contents.[216] The suitcases were being transported by the Emir of Gwandu, whose son was Buhari's aide-de-camp, and were cleared through customs on 10 June 1984 without inspection during his return flight from Saudi Arabia.[217]

PTF allocation to the military

[edit]While Buhari was Chairman of the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF), critics had questioned the PTF's allocation of 20% of its resources to the military, which they feared would not be accountable for the revenue.[218][219]

Akhaine, Saxone (27 August 2001) Nigeria: Buhari Calls for Sharia in All States Archived 23 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. He was quoted in 2001 as saying, "I will continue to show openly and inside me the total commitment to the Sharia movement that is sweeping all over Nigeria", he then added: "God willing, we will not stop the agitation for the total implementation of the Sharia in the country."[220] Buhari has denied all allegations that he has a radical Islamist agenda.[221] On 6 January 2015, Buhari said: "Because they can't attack our record, they accuse me falsely of ethnic jingoism; they accuse me falsely of religious fundamentalism. Because they cannot attack our record, they accuse us falsely of calling for election violence – when we have only insisted on peace. Even as Head of State, we never imposed Sha'riah."[222]

Mediation with Boko Haram

[edit]In 2012, Buhari's name was included on a list published by Boko Haram of individuals it would trust to mediate between the group and the Federal Government.[223] However, Buhari strongly objected and declined to mediate between the government and Boko Haram. In 2013, Muhammadu Buhari made a series of statements, when he asked the Federal Government to stop the killing of Boko Haram members and blamed the rise of the terrorist group on the prevalence of Niger Delta militants in the South. Buhari stated[224] that "what is responsible for the security situation in the country is caused by the activities of Niger Delta militants [...] The Niger Delta militants started it all".[225] He also questioned the special treatment including close to $500 million a year paid to 30,000 militants under the amnesty programme since 2013[226] by the Federal Government and deplored the fact that Boko Haram members were killed and their houses destroyed.

Abolishing the office of the first lady

[edit]In December 2014, Muhammadu Buhari went on the record to say he would abolish the office of the First Lady if he was elected as president, claiming it was unconstitutional.[227][228]

The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), a Nigerian militant group that endorsed Buhari during the 2015 general elections, commended Buhari for his plans and went on to say that the office of the First Lady was "obviously an irrelevant, fraudulent and unconstitutional office, whose only purpose is to further plunder the resources of the country."[229]

Since assuming the presidency on 29 May 2015, Buhari has yet to terminate the office of the First Lady. Aisha Buhari operates from the office of the First Lady as "wife of the President".[230]

Having suggested the abolition of the office of the First Lady,[228] Buhari has further aired some controversial statements about women.

During a visit to Germany, and standing next to German Chancellor Angela Merkel,[231] Buhari reiterated "I don't know which party my wife belongs to, but she belongs to my kitchen and my living room and the other room" [232] after his wife had earlier advised him to step up his leadership.[232]

Plagiarism scandal

[edit]In September 2016, President Buhari came under heavy criticism after a newspaper report found him using plagiarized speech during the launching of a national re-orientation campaign tagged "Change begins with me". The speech was later found to be lifted from the 2009 inaugural speech of former US President Barack Obama.[233][234] The presidency later apologized and says the blunder was caused by "overzealous staff" and "Those responsible" will be sanctioned.[235][236] However, one week later, a deputy director in the State House linked to the speech was redeployed and presidency assured Nigerian public that it has taken steps to avoid a repeat of such an embarrassing occurrence by implementing digital tools that detect plagiarism.[237]

Twitter Ban

[edit]After Buhari made a Twitter post threatening violence against the Biafra insurgents in southeast Nigeria on 5 June 2021, Twitter deleted his comments as violations of its terms of service. Shortly thereafter, the Nigerian government banned Twitter from the country entirely.[238] They lifted the ban on 13 January 2022, after they said Twitter had agreed to register its operations in Nigeria and pay tax.[239]

Signature Forgery Scandal

[edit]As part of the discovery made in a lawsuit levelled against the former CBN Governor of Nigeria, Godwin Emefiele, Boss Mustapha, a senior official in ex-President Buhari's administration, testified that three suspects allegedly stole $6.2m (£4.9m) from the central bank, using the forged signature of then President Muhammadu Buhari.[240]

Personal life

[edit]Family

[edit]

In 1971, Buhari married his first wife, Safinatu (née Yusuf). They had five children together, four girls and one boy. Their first daughter, Zulaihat (Zulai) was named after Buhari's mother. Their other children are Fatima, Musa (deceased son), Hadiza, and Safinatu.[241] In 1988, Buhari and his first wife Safinatu divorced. On 14 January 2006, Safinatu died from complications of diabetes. In November 2012, Buhari's first daughter, Zulaihat (née Buhari) Junaid died from sickle cell anaemia, two days after having a baby at a hospital in Kaduna.[242]

In December 1989, Buhari married his second and current wife Aisha Buhari (née Halilu). They also had five children together, a boy and four girls: Aisha, Halima, Yusuf, Zahra "Zarah" and Amina.[243] Yusuf married Zahra Nasir Bayero, the daughter of Emir Nasiru Ado Bayero, in August 2021.[244]

Buhari is a Muslim.

Wealth

[edit]In 2015, Buhari declared US$150,000 cash; in addition to five homes and two mud houses as well as farms, an orchard and a ranch of 270 head of cattle, 25 sheep, five horses and a variety of birds, shares in three firms, two undeveloped plots of land, and two cars bought from his savings.[245]

Honours

[edit]National honours

[edit] Nigeria:

Nigeria:

Grand Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (GCFR) (1983)

Grand Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (GCFR) (1983)

Foreign honours

[edit] Benin:

Benin:

Grand Cross of the National Order of Benin (2015)

Grand Cross of the National Order of Benin (2015)

Equatorial Guinea:

Equatorial Guinea:

Grand Collar of the Order of Independence (2016)[246]

Grand Collar of the Order of Independence (2016)[246]

Guinea Bissau:

Guinea Bissau:

Recipient of the Medal of Amílcar Cabral (8 December 2022)[247]

Recipient of the Medal of Amílcar Cabral (8 December 2022)[247]

Liberia:

Liberia:

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia (27 July 2019)[248][249]

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia (27 July 2019)[248][249]

Niger:

Niger:

Grand Cross of the National Order of Niger (17 March 2021)[250]

Grand Cross of the National Order of Niger (17 March 2021)[250]

Portugal:

Portugal:

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (30 June 2022)[251]

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (30 June 2022)[251]

Senegal:

Senegal:

Grand Cross of the National Order of the Lion (7 July 2022)[252]

Grand Cross of the National Order of the Lion (7 July 2022)[252]

Serbia:

Serbia:

Second Class of the Order of the Republic of Serbia (2016)

Second Class of the Order of the Republic of Serbia (2016)

Traditional titles

[edit]In 2017, the South-East council of traditional rulers honoured President Buhari with the chieftaincy titles of the Enyioma I of Ebonyi and the Ochioha I of Igboland.[253] At the time of his investiture, the president had already held a title—that of the Ogbuagu I of Igboland—in the Nigerian chieftaincy system.[254] He was later awarded another one, Ikeogu I of Igboland, in the following year.[255][256]

See also

[edit]- List of heads of state of Nigeria

- List of Nigerians

Biography portal

Biography portal Nigeria portal

Nigeria portal Politics portal

Politics portal- List of Hausa people

References

[edit]- ^ a b Paden, John (2016). Muhammadu Buhari: The Challenges of Leadership in Nigeria. Roaring Forties Press. ISBN 978-1-938901-64-5.

- ^ "Muhammadu Buhari | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 29 May 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "President Buhari's inaugural speech on May 29, 2015". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 29 May 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Military Regime of Buhari and Idiagbon, January 1984 – August 1985". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Max Siollun (October 2003). "Buhari and Idiagbon: A Missed Opportunity for Nigeria". Dawodu.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Sanusi Lamido Sanusi (22 July 2002). "Buharism: Economic Theory and Political Economy". Lagos. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Mohammed Nura (14 September 2010). "Nigeria: The Spontaneous 'Buharism' Explosion in the Polity". Leadership (Nigeria). Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "The frustrations of Buhari from 2003 to 2011". Vanguard News. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Nigeria election: Muhammadu Buhari wins presidency". BBC News. 1 April 2015. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Buhari in historic election win, emerges Nigeria's President-elect | Premium Times Nigeria". 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Muhammadu Buhari". The Muslim 500. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "UPDATED: Buhari wins second term". Punch Newspapers. 27 February 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Stephanie Busari and Aanu Adeoye, for (27 February 2019). "Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari reelected, but opponent rejects results". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Nigeria's Buhari wins re-election, rival pursues fraud claim". Reuters. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ The Guardian: "Muhammadu Buhari: reformed dictator returns to power in democratic Nigeria" by David Smith Archived 5 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine 31 March 2015

- ^ "Muhammadu Buhari Presidential Candidate". thisisbuhari.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "Muhammad Buhari". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Kperogi, Farooq. "Buhari's surname not his father's name; how he dumped it". P.M. News. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive Interview With GMB – Buhari speaks to The Sun Newspaper". Facebook. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Major General Muhammadu Buhari (retd.) Archives". Punch Newspapers. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Obotetukudo, Solomon (2011). The Inaugural Addresses and Ascension Speeches of Nigerian Elected and Non elected presidents and prime minister from 1960 -2010. University Press of America. p. 90.

- ^ Ogbebor, Paul Osakpamwan (26 November 2012). "The Nigerian Defence Academy – A Pioneer Cadet's Memoir". Vanguard (Nigeria). Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Agbese, Dan (2012). Ibrahim Babangida: The Military, Power and Politics. Adonis & Abbey Publishers, 2012. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-906704-96-4.

- ^ Luckham, Robin (1971). The Nigerian Military a Sociological Analysis of Authority & Revolt 1960–1967. CUP Archive, 1971. p. 235. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ The Times, "US overtakes Britain at educating leaders" (5 September 2019), pg. 19

- ^ "General Muhammadu Buhari: The dawn of a new era". Businessday NG. 31 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Prominent Nigerians who share birthday month with President Buhari". guardian.ng. 18 December 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 343.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 339.

- ^ a b Momoh 2000, p. 340.

- ^ Momoh 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Siddhartha Mitter (28 October 2015). "India can rival China in Nigeria, by being exactly what China is not: Open and free". Quartz. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Solomon Williams Obotetukudo (2010). The Inaugural Addresses and Ascension Speeches of Nigerian Elected and Non-Elected Presidents and Prime Minister, 1960–2010. University Press of America. pp. 91–92.

- ^ "Nigeria : Constitution and politics". Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "PRESIDENT MUHAMMADU BUHARI (GCFR) | Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike". Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Nigeriaroute.com". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "This is how the 36 states were created". 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Alapiki, Henry E (2005). "State Creation in Nigeria: Failed Approaches to National Integration and Local Autonomy". African Studies Review. 48 (3): 49–65. doi:10.1353/arw.2006.0003. JSTOR 20065139. S2CID 146571948.

- ^ "Matthews, Norman Derek, (19 March 1922–21 July 1976), Governor of Montserrat, since 1974", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u157278, retrieved 17 September 2023

- ^ "History of the Nigerian Petroleum Industry". Nigerian National Petroleum Company. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria's Oil Production on Increase." Afro-American (1893–1988): 16. 16 December 1978.

- ^ Muhammed Kabir Hassan (31 December 2014). "Nigeria: The Mess 'Full Literates' Have Put Us All In!". AllAfrica. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "A Rejoinder To 'Semi-Illiterate' PDP Secretary Prof. Wale Oladipo By Dr. M.K. Hassan". 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ The Source Magazine Online Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Thesourceng.com. Retrieved on 4 November 2016.

- ^ Matthews, Martin P. Nigeria: current issues and historical background. p. 121.

- ^ "No to another Republic of Nigerian Army!". guardian.ng. 3 September 2023. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ a b Graf 1988, p. 149.

- ^ Graf 1988, p. 150.

- ^ a b Graf 1988, p. 153.

- ^ "Nigeria: Repeal of Decree 2". refworld.org. 1 October 1998. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "THE UNTOLD TALES OF GEN. BUHARI ... [a must read]". Naija Politica. 4 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015.

- ^ a b c "Nigeria's Muhammadu Buhari in profile". BBC News. 17 April 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Nigeria: Human Rights Watch Africa". africa.upenn.eu. 10 May 1996. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Fela Kuti, PoC, Nigeria" (PDF). amnesty.org. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2015.

On numerous occasions he was detained and harassed by the authorities

- ^ Ogbondah, Chris (1991). "Origins and Interpretation of Nigerian Press Laws" (PDF). Africa Media Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "My Stance On 'Non Disclosure' Remains Unshakable – Tunde Thompson". nationalnetworkonline.com. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015.

- ^ "CCT Chairman Advocates Return of Decree 2 to punish Journalists".

- ^ a b Nwachuku, Levi Akalazu; G. N. Uzoigwe (2004). Troubled Journey: Nigeria Since the Civil War. University Press of America. p. 192.

- ^ Graf 1988, p. 162.

- ^ Vreeland, James Raymond (19 December 2006). The International Monetary Fund: Politics of Conditional Lending. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-415-37463-7.

Buhari proved his independence by pushing through economic austerity so severe it went beyond what many advised – all the while he refused IMF assistance.

- ^ Mathews, Martin P. (1 May 2002). Nigeria: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science Publishers, Inc. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-59033-316-7. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Graf 1988, p. 164.

- ^ "Nigeria's Muhammadu Buhari in profile". bbc.co.uk. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Clifford D. May (10 August 1984). "Nigeria's discipline campaign: Not sparing the rod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Graf 1988, p. 154.

- ^ "Security and Anticrime Measures". country-data.com. June 1991. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Buhari: History and the Wilfully Blind". thisdaylive.com. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Muhammadu Buhari, Nigeria's Strictest Leader". abiyamo.com. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Expelled foreigners pouring out of Nigeria By The Associated Press". The New York Times. 5 May 1985.

- ^ "Présidentielle nigériane : Muhammadu Buhari affrontera Goodluck Jonathan". jeuneafrique.com. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "The crimes of Buhari-Wole Soyinka". saharareporters.com. 14 January 2007. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ My contract with Nigeria – Buhari. vanguardngr.com (17 March 2015)

- ^ "Muhammadu Buhari". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Heaton, Matthew M. (2008). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139472036.

- ^ "Buhari: Most part of my detention was in a small bungalow in Benin". TheCable. 7 November 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Nwachukwu, John Owen (16 May 2017). "How Ibrahim Babaginda sent bags of money to Buhari - John Parden". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Development: PTF – shining in the gloom". June 1998. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Nigeria: Facts and figures". BBC News. 17 April 2007. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ "Buhari at 69: The leader Nigeria lacks - Daily Trust". dailytrust.com. 18 December 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Huge win for Nigeria's Yar'Adua" Archived 26 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 23 April 2007.

- ^ Felix Onuah and Camillus Eboh, "Nigerian president picks ministers", Reuters (IOL), 4 July 2007.

- ^ Emeka Mamah (18 March 2010). "Buhari Joins Congress for Progressive Change". Vanguard. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Summary of the 2011 Presidential election results". Archived from the original on 29 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Nigerian Religious Leaders Advise Political Candidates". cfr.org. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Soyombo, Fisayo (31 December 2014). "Opinion Will Muhammadu Buhari be Nigeria's next president?". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

In 2011, Buhari was accused of inciting the violence that followed his loss to Jonathan. The following year, he said "the dog and the baboon would all be soaked in blood" should the 2015 election be rigged. Buhari has shed blood before for his presidential ambition, some people believe. And they think he would do it again. Such a man, they reason, should never taste power.

- ^ Ndujihe, Clifford; Idonor, Daniel (11 October 2011). "Post-election violence: FG panel report indicts Buhari". vanguardngr.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Buhari's Presidential Attempts And 2015 Chances". naij.com. November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Festus Owete (21 April 2011). "Congress for Progressive Change considers going to court and Buhari declared that he will make Nigeria ungovernable for Jonathan. Since then the Boko Haram Sect has been bombing Nigerians". Next. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Buhari will not probe past corrupt Nigerian leaders if they repent – APC". premiumtimesng.com. 29 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "#Nigeria2015: Jonathan wants Buhari disqualified". premiumtimesng.com. 11 January 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Buhari: Certificate nuisance!". vanguardngr.com. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Ajasa, Femi. (8 May 2014) BUHARI TO BOKO HARAM: You're bigots masquerading as Muslims – Vanguard News Archived 9 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Vanguardngr.com. Retrieved on 4 November 2016.

- ^ Muhammed, Garba. (24 July 2014) Suicide bombs in Nigeria's Kaduna kill 82, ex-leader Buhari targeted Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Reuters. Uk.reuters.com. Retrieved on 4 November 2016.

- ^ Nigeria Opposition Leader Vows to Improve Security Archived 16 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Voanews.com (12 December 2014). Retrieved on 4 November 2016.

- ^ "MEND replies PDP, says Buhari best candidate". punchng.com. 9 January 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria: l'ex-président Olusegun Obasanjo lâche Goodluck Jonathan". RFI. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Colin Freeman (31 March 2015). "Muhammadu Buhari claims victory in Nigeria's presidential elections". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Historic succession complete as Buhari is sworn in as the president of Nigeria | Nigeria | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Nigeria Presidential Elections Results 2019". BBC News. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Oyeyemi, Tunji (29 May 2019). "2019 Presidential Inauguration Ceremony". FMIC. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ a b Erezi, Dennis (29 May 2019). "Buhari sworn in for second term". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Nigerians got poorer in Muhammadu Buhari's first term". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Obadare, Ebenezer (2019). "Introduction: Nigeria – Twenty years of civil rule". African Affairs. 121 (485): e75–e86. doi:10.1093/afraf/adz004.

- ^ a b c d e "Executive exerts its privilege". Africa Confidential. 60 (17). 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019."Executive exerts its privilege". Africa Confidential. 60 (17). 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ a b "The Gang of 43 breaks cover". African Confidential. 60. 26 July 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Adetayo, Olalekan (22 May 2016). "Buhari cancels two-day state visit to Lagos". The Punch. Abuja. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Nwabughuiogu, Levinus (6 June 2016). "Buhari heads to London for medical treatment". Vanguard News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Ifijeh, Martins (9 June 2016). "Nigeria: Meniere's Disease and Buhari's Health". Thisday Live. All Africa. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Buhari Travelled Abroad Over Poor Health – Nigerians". Naij. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.