Rob Roy (1995 film)

| Rob Roy | |

|---|---|

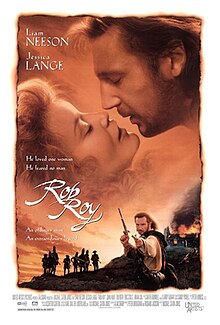

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Caton-Jones |

| Screenplay by | Alan Sharp |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Walter Lindenlaub |

| Edited by | Peter Honess |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 139 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $28 million[1] |

| Box office | $58.7 million[2] |

Rob Roy is a 1995 historical biographical drama film directed by Michael Caton-Jones.[3] It stars Liam Neeson as Rob Roy MacGregor, an 18th-century Scottish highlander who becomes engaged in a dispute with a nobleman in the Scottish Highlands, played by John Hurt. Tim Roth won the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Archibald Cunningham, one of Rob Roy's chief antagonists. Jessica Lange portrays Roy's wife, and Eric Stoltz, Brian Cox, and Jason Flemyng play supporting parts.

The film is dedicated to two Scotsmen: film director Alexander MacKendrick and football player and manager Jock Stein.

Plot

[edit]The film is set in Scotland, 1713, with a fictionalised Robert Roy MacGregor, of Clan MacGregor, as its main protagonist. Although providing the Lowland gentry with protection against cattle rustling, he barely manages to feed his people. Hoping to alleviate their hunger and his poverty, MacGregor borrows £1,000 from James Graham, Marquess of Montrose, to establish himself as a cattle raiser and trader.

Wanting to leave England to flee legal troubles, his anglicized aristocrat relative Archibald Cunningham is sent to stay with Montrose. Cunningham is a supremely skilled swordsman, so Montrose makes money off Cunningham by making wagers on sword contests that Cunningham's haughty manner and effeminate bearing bring upon himself. Cunningham learns about MacGregor's money deal from Montrose's factor Killearn, and murders MacGregor's friend, Alan McDonald, to steal the money. MacGregor requests time from Montrose to find McDonald and the money. Montrose offers to waive the debt if MacGregor will testify falsely that Montrose's rival John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll is a Jacobite. MacGregor refuses and Montrose vows to imprison him in the tolbooth until the debt is repaid. After MacGregor flees, Montrose seizes MacGregor's land to cover the debt, declaring him an outlaw and ordering Cunningham to bring him in "broken, but not dead". Redcoats slaughter MacGregor's cattle, burn his croft, and Cunningham rapes his wife Mary.

Mary understands that Cunningham intends to flush her husband out of hiding and makes his brother, Alasdair, who arrives too late to save her, swear to conceal knowledge of the rape. MacGregor refuses to permit his clan to wage war on Montrose, and instead decrees to harm Montrose financially. Betty, a maidservant at Montrose's estate, has become pregnant with Cunningham's child. When Killearn tells Montrose, Betty is dismissed from service and rejected by Cunningham. Betty seeks refuge with the MacGregors, revealing that she overheard Killearn and Cunningham plot to steal the money. To build a case against Cunningham, MacGregor abducts Killearn and imprisons him upon Factor's Island in Loch Katrine. Mary promises Killearn that he will be spared if he testifies against Cunningham, but Killearn taunts her with her rape. Realizing that Mary is pregnant, he threatens to tell MacGregor that Cunningham may be the father if she does not release him, leading Mary and Alasdair to kill him.

Montrose tells Cunningham that he suspects who really stole the money but does not care. Cunningham and the redcoats burn the Clan's crofts. MacGregor refuses to take the bait, but Alasdair attempts to snipe Cunningham and hits a redcoat. The redcoats shoot both Alasdair and another Clan member, Coll. Alasdair finally tells MacGregor about Mary's rape. Taken prisoner, MacGregor accuses Cunningham of murder, robbery and rape. Cunningham confirms the charges, and gleefully beats and tortures MacGregor. The following morning, Montrose orders MacGregor hanged from a nearby bridge. MacGregor loops the rope binding his hands around Cunningham's throat and then jumps off the bridge; he escapes when the rope is cut to save Cunningham.

Mary gains an audience with the Duke of Argyll and exposes Montrose's plan to frame him. Moved by MacGregor's integrity, the Duke grants the family asylum on his estate at Glen Shira. MacGregor arrives, at first upset by Mary's unwillingness to inform him of her rape or her pregnancy but later willing to raise the child as his own. The Duke arranges a duel between MacGregor and Cunningham, wagering Montrose that if MacGregor lives, his debt will be forgiven and that if he dies, the Duke will pay his debt. Montrose agrees and Cunningham and MacGregor vow that no quarter will be asked or given. Armed with a light and swift small sword-like rapier, Cunningham repeatedly wounds MacGregor, who appears to quickly exhaust himself swinging a heavy broadsword. MacGregor seems defeated, but when Cunningham showboats to deliver a theatrical killing blow, MacGregor seizes his enemy's sword-point. As Cunningham struggles to free his blade, one stroke from MacGregor's broadsword splits Cunningham's torso. Now free of debts and with his honor intact, he returns home to his wife and children.

Cast

[edit]- Liam Neeson as Rob Roy MacGregor

- Jessica Lange as Mary MacGregor

- John Hurt as James Graham, 4th Marquess of Montrose

- Tim Roth as Archibald Cunningham

- Eric Stoltz as Alan McDonald

- Andrew Keir as John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll

- Brian Cox as Killearn

- Brian McCardie as Alasdair MacGregor

- Gilbert Martin as Guthrie, the Duke of Argyll's fencing champion

- Jason Flemyng as Gregor, a MacGregor Clan retainer

- Ewan Stewart as Coll, a MacGregor Clan retainer

- David Hayman as Tam Sibbalt, a Scottish Traveller who has been rustling from cattle herds under MacGregor's protection

- Shirley Henderson as Morag

- Vicki Masson as Betty

Production

[edit]According to screenwriter Alan Sharp, Rob Roy was conceived as a Western set in the Scottish Highlands.[4]

The film was shot entirely on location in Scotland, much of it in parts of the Highlands so remote they had to be reached by helicopter. Some of the scenes were filmed in Glen Coe, Glen Nevis, and Glen Tarbert.[5] In the opening scenes, Rob and his men pass by Loch Leven. Loch Morar stood in for Loch Lomond, on the banks of which the real Rob Roy lived. Scenes of the Duke of Argyll's estate were shot at Castle Tioram, the Marquess of Montrose's at Drummond Castle. Shots of "The Factor's Inn" were filmed outside Megginch Castle. Crichton Castle was used in a landscape shot.

Non-stop Highland rain presented a problem for cast and crew when filming outdoor shots, as did the resulting swarms of midges.

William Hobbs choreographed the swordfights,[6] with Robert G. Goodwin consulting.

The main composer is Carter Burwell.[7] Beside the film score, the film features a slightly different version of a traditional Gaelic song called "Ailein duinn", sung in the film by Karen Matheson, lead singer in Capercaillie.[8]

Historical accuracy

[edit]Details of Rob Roy's life are a mix of fact and legend, and according to one historian, the film portrays Rob Roy "in the most sympathetic light possible".[9] Not all of the events shown in the film were real. The narration covers approximately the years 1712 to 1722; nevertheless the uprisings of 1715 and 1719 were not depicted in the film.[10]

MacGregor had business dealings with Montrose for ten years before the loan of £1000 went missing. Though called the Marquess of Montrose, James Graham, 4th Marquess of Montrose had already been elevated to Duke of Montrose at this point in history. He was raised to the dukedom as a reward for his support for the Act of Union, whilst being Lord President of the Scottish Privy Council.

The character of Cunningham is fictional,[11][12][13][14] though certainly based upon Henry Cunningham Esq. of Boquhan, described by Sir Walter Scott as a "daring character with an affectation of delicacy of address and manners amounting to foppery," who nonetheless seized a sword and "rushed on the outlaw with such unexpected fury that he fairly drove him off the field."[15]

The uniforms of the English soldiers derive from an era after the story told. At that time the coattails were longer in size and had not yet been turned back.[16] The regiments were not numbered until 1751, but in the movie the backs of the mitre caps of the grenadiers show clearly the number 49 (for the 49th Regiment of Foot). However, this regiment was only put up in 1743, long after the story described.[17]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]United Artists gave Rob Roy a limited release in the United States and Canada on April 7, 1995, and the film grossed $2,023,272 from 133 theaters for the weekend. Five days later it expanded to 1,521 theaters and grossed $7,190,047 for the weekend, ranking number 2 at the US box office behind Bad Boys. Rob Roy's widest release during its theatrical run was 1,885 theaters, and the film grossed $31,596,911 in the United States and Canada.[18] Internationally it grossed $27.1 million for a worldwide total of $58.7 million.[2]

Critical reception

[edit]Rob Roy received a generally positive critical response. On Rotten Tomatoes, it has an approval rating of 73% based on reviews from 44 critics, with an average score of 6.4 out of 10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Rob Roy is an old-fashioned swashbuckler that benefits greatly from fine performances by Liam Neeson, Jessica Lange, and Tim Roth."[19] On Metacritic it has an average score of 55 out of 100, based on reviews from 19 critics.[20] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade "B+" on scale of A+ to F.[21]

Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, said, "This is a splendid, rousing historical adventure, an example of what can happen when the best direction, acting, writing and technical credits are brought to bear on what might look like shopworn material." Ebert said the film's outline could have led to "yet another tired" historical epic, but he found that the director was able to produce "intense character studies". The critic applauded Tim Roth's performance, calling it "crucial" to the film's success. Ebert was also impressed by the climactic sword fighting scene, which had been choreographed by fight director William Hobbs, and called it "one of the great action sequences in movie history".[22] His partner Gene Siskel agreed, calling it the "best sword fight in motion picture history."[23]

In contrast, Rita Kempley of The Washington Post compared Rob Roy negatively to the action films Death Wish (1974) and First Blood (1982). Kempley disliked the film's violence and wrote, "Frankly, Rob Roy is about as bright as one of his cows. He doesn't even recognize that his obsession with honor will lead to the destruction of his clan." The critic found the protagonist unheroic in his mission for vengeance. Of his enemy, she said, "The villains, played with glee, manage to perk up the glacial pace, but they too grow tiresome."[24]

In The New York Times, Janet Maslin gave a mixed review of the film. She complained of the film's "long, dry stretches" and that the "plot [was] too ponderous and uninteresting for the film's visual sweep". Maslin said one of the film's saving graces was the "robust" presence of Liam Neeson, taller than those who played his enemies, and his character's charismatic exchange with Jessica Lange's character, writing, "Rob Roy is best watched for local color and for its hearty, hot-blooded stars." Maslin acknowledged that Neeson was "a far cry from the dour-looking Scottish drover who was the real Rob Roy" and said that the film failed to convey the figure's importance to audiences. The critic highlighted the scene of Cunningham raping Mary as one of the film's "strongest scenes" which was appropriately responded to by the "cowboy justice" of Neeson's lonesome and avenging Rob Roy.[25]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Name | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAFTA Film Awards[26] | Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role | Tim Roth | Won |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards[27] | Best Supporting Actor | Won | |

| Academy Awards[28] | Best Supporting Actor | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[29] | Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Nominated |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Archibald Cunningham – Nominated Villain[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rob Roy (1995)". The Wrap. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Klady, Leonard (February 19, 1996). "B.O. with a vengeance: $9.1 billion worldwide". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Williams, Karl. "Rob Roy". AllMovie. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ Minsaas, Kirsti (8 October 2012). "Rob Roy: The value of honor". The Atlas Sphere. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ "Top 12 Movies Filmed in Scotland (With Some Surprises!)". Hillwalk Tours. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (20 July 2018). "William Hobbs, Fight Director on Swashbuckling Classics 'The Duellists' and 'Rob Roy'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Interview With Carter Burwell, Composer". Musicnotes. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Carter Burwell - offbeat, dark and weird". Music Files. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Ross, David. "Rob Roy Biography". Britain Express. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex (14 January 2010). "Rob Roy: a Highland fling where they've flung out the history". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Rob Roy". Britannica. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Necker, Louis Albert (2021). A Voyage to the Hebrides, or Western Isles of Scotland;: With Observations on the Manners and Customs of the Highlanders. HardPress Limited. p. 80. ISBN 978-0371968079.

- ^ Duncan, John. "Robert the Red ( Rob Roy)". Scottish History Online. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "A Short History of Clan MacGregor and Rob Roy MacGregor". Heart O' Scotland. Archived from the original on August 5, 2002. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Scott, Sir Walter (1829). Rob Roy. Edinburgh: Cadell & Co. pp. xlvii–xlviii.

- ^ Michael Barthorp: The Jacobite Rebellions 1689-1745 (Men at Arms, Vol. 118), Osprey Publ./Bloomsbury Publ. 1982, ISBN 978-0850454321

- ^ "49th (Princess Charlotte of Wales's) (or the Hertfordshire) Regiment of Foot". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Rob Roy (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ "Rob Roy". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ "Rob Roy reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2021-02-11.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (April 7, 1995). "Rob Roy". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Siskel & Ebert Collection on Letterman, Part 5 of 6: 1995-96, 23 July 2019, retrieved 2022-10-27

- ^ Kempley, Rita (April 7, 1995). "'Rob Roy' (R)". The Washington Post.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 7, 1995). "Film Review: Rob Roy; Liam Neeson: Man in Kilts". The New York Times.

- ^ "Film - Actor in a Supporting Role 1996". bafta.org. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "1995 Awards". Kansas City Film Critics Circle. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Here's Complete List of Oscar Nominees". Chicago Tribune. February 14, 1996. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "Rob Roy". Golden Globes. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 2016-08-06.

External links

[edit]- 1995 films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s historical films

- 1995 romantic drama films

- American biographical drama films

- American epic films

- British biographical drama films

- British epic films

- Remakes of American films

- American romantic drama films

- British romantic drama films

- Cultural depictions of Rob Roy MacGregor

- Drama films based on actual events

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films scored by Carter Burwell

- Films about families

- Films about miscarriage of justice

- Films about murder

- Films about outlaws

- Films about poverty in the United Kingdom

- Films about rape in the United Kingdom

- American films about revenge

- Films directed by Michael Caton-Jones

- Films set in Highland (council area)

- Films set in 1713

- Films set in the 1720s

- Films shot in Scotland

- Romance films based on actual events

- American swashbuckler films

- United Artists films

- American historical romance films

- British historical romance films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s British films

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language romantic drama films

- English-language historical films